JavaOne 2015 saw a series of talks by the Project Jigsaw team about modularity in Java 9. They are all very interesting and full of valuable information and I urge every Java developer to watch them.

Beyond that I want to give the community a way to search and reference them, so I summarize them here:

- Prepare For JDK 9

- Introduction To Modular Development

- Advanced Modular Development

- Under the Hood Of Project Jigsaw

I made an effort to link to as many external resources as possible to keep the individual posts short. The play icons will take you straight to the corresponding point in the ten hour long video streams that Oracle put online for each room and day. (Great format, folks!) Not only did they (so far) fumble the cutting, they also seem to have resorted to low-volume mono sound so make sure to crank up the volume.

Let's top the series off with a peek under the hood of the Java Platform Module System!

- Content: A technical investigation of the module system's mechanisms

- Speaker: Alex Buckley

- Links: Video and Slides

▚Accessibility & Readability

Alex Buckley reiterates how public no longer means "publicly accessible to everyone".

By default, public classes will be inaccessible outside of their module.

Only by exporting the containing package do they become accessible.

If the export is qualified, then this is only true for the specificly mentioned modules.

▚Accessibility and Class Loaders

Class loaders can be used to prevent classes from one package to see classes from another. Lacking a better mechanism this is currently used to simulate limited accessibility and strong encapsulation.

But if looked at closer, it becomes apparent that this mechanism can not fulfill those promises.

As soon as a piece of codes gets hold of a Class object, it can use it to create more instances via reflection.

It is also not a feasible solution to use inside the JVM as spinning up a complex web of class loaders is a compatibility nightmare.

Strong encapsulation is about being able to prevent access even if the accessing class and the target class are in the same class loader and even if someone is using core reflection to manipulate class objects.

▚The Role Of Readability

The essential concepts of readability and accessibility, as defined in The State Of The Module System (SOTMS), are independent of class loaders.

That means that accessibility works at compile time, when there aren't any class loaders, and that one can reason about it solely based on the static information in module-info.java.

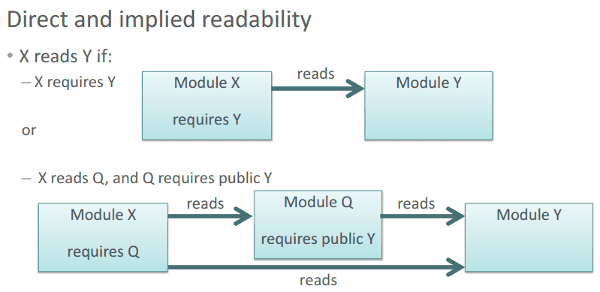

Buckley goes on to discuss implied readability and how it can be used to refactor modules. This feature allows a module to split off some of its functionality into a separate module without its clients noticing. While this allows what Buckley calls "downwards decomposability" a module can not be deleted and have its role filled by another module. So modules can not be merged without breaking clients.

▚Core Reflection

Strong encapsulation is upheld by reflection. It is not possible to access a member of a type in a non-exported package. Not even with setAccessible(true), which in fact performs the same checks as compiler and VM to check accessibility.

▚Different Kinds Of Modules

Buckley presents the three kinds of modules:

Named Modules:

Contain a module-info.java and are loaded from the module path.

Only their exported packages are accessible and they can only require and thus read other named modules (which excludes the unnamed module).

Unnamed Module: The unnamed module contains of all the classes from the class path. All packages are exported and they read all modules.

Automatic Modules:

Automatic, or automatically named, modules are JARs without a module-info.java that were loaded from the module path.

Their name is derived from the JAR file name, they export every package and read any module, including other automatic ones and the unnamed module.

So like described in application migration, automatic modules are the only way for modules to read unmodularized JARs.

This apparent detour was chosen to prevent the well-formed module graph to depend on the arbitrary contents of the class path.

Interestingly enough, a named module can require public an automatic module, which means it exports all of its types to its dependencies as discussed in implied readability.

Buckley describes automatic modules as a necessary evil akin to raw types in generics. They are necessary because they enable migration and evil because of their hidden complexity, which hopefully doesn't leak to users.

▚Loaders And Layers

▚Class Loading

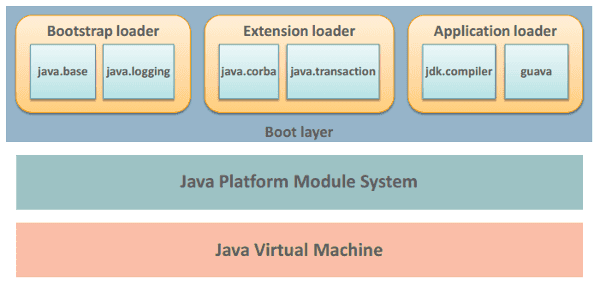

The talk's third part starts with a clear message: Class loading doesn't change! In fact the module system operates beneath the class loading mechanism and the known three loaders continue to work as they do now except for some implementation details.

Most JDK modules will be loaded by the boot loader, a few by the extension loader, and a handful of tool-related modules by the application/system loader. Since the boot loader runs will all permissions, security can be improved by moving modules out of the boot loader. This deprivileging work will continue throughout JDK 9 and 10.

▚Layers

Buckley goes on to describe layers, which SOTMS mentions only briefly. A layer is created from a module graph and a mapping from modules to class loaders - see its documentation for details. Creating a layer informs the JVM about the modules and their contained packages so that it knows where to load classes from when they are required.

The module system enforces the following constraints on the module graph and the mapping from modules to class loaders.

▚Well-Formed Graphs

Module graphs are directed graphs and they must be acyclic. Additionally, a module can not read two or more modules that export the same package.

▚Well-Formed Maps

Because a class loader can not load two classes with the same fully qualified name, the broad decision was made that any two modules with the same package (exported or concealed) can not be mapped to the same class loader. Trying this fails with an exception.

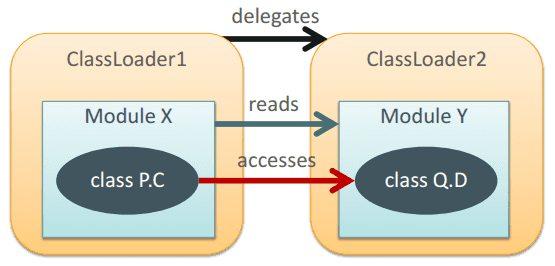

Furthermore at runtime class loader delegation must respect module readability.

Since the module graph is acyclic one might think that class loader delegation is, too. Buckley gives an example from the JDK where this is assumption is wrong. It boils down to having three modules, each reading the next but a single class loader for the first and last, thus creating a cycle between the two loaders.

Next, Buckley discusses the problem of split packages, which occurs when multiple loaders define classes for the same package. Since class loader delegation will respect module readability, a loader can not delegate to two different loaders for the same package.

He presents the example of JSR 305 and Xerxes in detail, which is worth watching.

▚Layers Of Layers

Layers can, surprise, be layered. Each layer, except the boot layer, has a parent so a layer tree emerges. Modules in one layer can read modules in their ancestor layers.

This gives frameworks the freedom to organize modules at runtime without upsetting their traditional uses of class loaders. It can also be used to allow multiple versions of the same module, partly addressing a recent pet peeve of mine. Because multiple versions only work out when controlled by a dedicated system, like an application server, this can not be achieved via command line.

Just as modules wrap up coherent sets of packages and interact with the VM's accessibility mechanism, layers wrap up coherent sets of modules and interact with the class loader's visibility mechanism. It will be up to frameworks to make use of layers in the next 20 years just as they have made use of class loaders in the first 20 years.

▚Summary Of Summaries

Four talks in three bullet points:

- In Java 9 there is strong encapsulation of modules by the compiler, VM, reflection.

- Unnamed and automatic modules help with migration.

- The system is safe by construction – no cycles or split packages.

▚Questions

▚Are Resources Also Strongly Encapsulated?

Yes, but there are discussions going on about that very topic. Follow the mailing list for details.

▚Can Non-Exported Instances Be Accessed Through An Exported Interface?

Yes! (Buckley was visibly excited to get a chance to answer that question.)

So a module that exports some type and returns instances of it from a method can instead return instances of any non-exported subtype. The caller can interact with it as long she does not try to cast it to the encapsulated subtype or use reflection to, e.g., create a new instance from it.

▚What Are The Performance Implications?

There is so much to say about that, Buckley can not go into it. Regarding accessibility, the JVM creates a nice lookup table and the checks are, performance-wise, basically a no-op.

▚What About Monkey Patching?

Assume there is a known bug in a library not under the one's control. Before Jigsaw, it was possible to fix the bug locally, put the new class on the class path and have it shadow the original one. Will that still work from Java 9 on?

Yes, as long as a module does not export the package containing the monkey patched class.

▚When Are The Access Checks Performed For Reflection?

The question was actually somewhat different but Buckley answered this one instead.

The general answer is, "as late/lazily as possible".

So getClass will always return an instance (even if the class is not accessible) and only when one uses it to access fields, methods or constructors that are not accessible, are the checks performed and possible exceptions thrown.

▚So Many More...

There a lot of other questions being asked. If you are interested in this topic, make sure to check them out.