Java 8 brought us lambda expressions and we're all very happy using them. But how do they work? What happens behind the scenes and how well do they perform? A talk by Brian Goetz, specification lead for the Java specification request which introduced lambda expressions, answers these questions.

This post is going to outline the talk "Lambdas in Java: A peek under the hood", which Brian Goetz held in October 2013 at the goto; conference in Aarhus. As usual for this series, some details are left out for brevity, so if you're interested, make sure to check out the video.

▚The Talk

Here's the talk:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLksirK9nnE

The slides can be found here.

▚The Gist

After a short introduction of lambdas, Brian Goetz presents some of the ideas the expert group for JSR 335 considered for their implementation. He talks about their type and their runtime representation, the advantages of the chosen approach and gives some numbers regarding its performance. He finishes the talk with an outlook on possible future optimizations.

▚Lambdas in Java 8

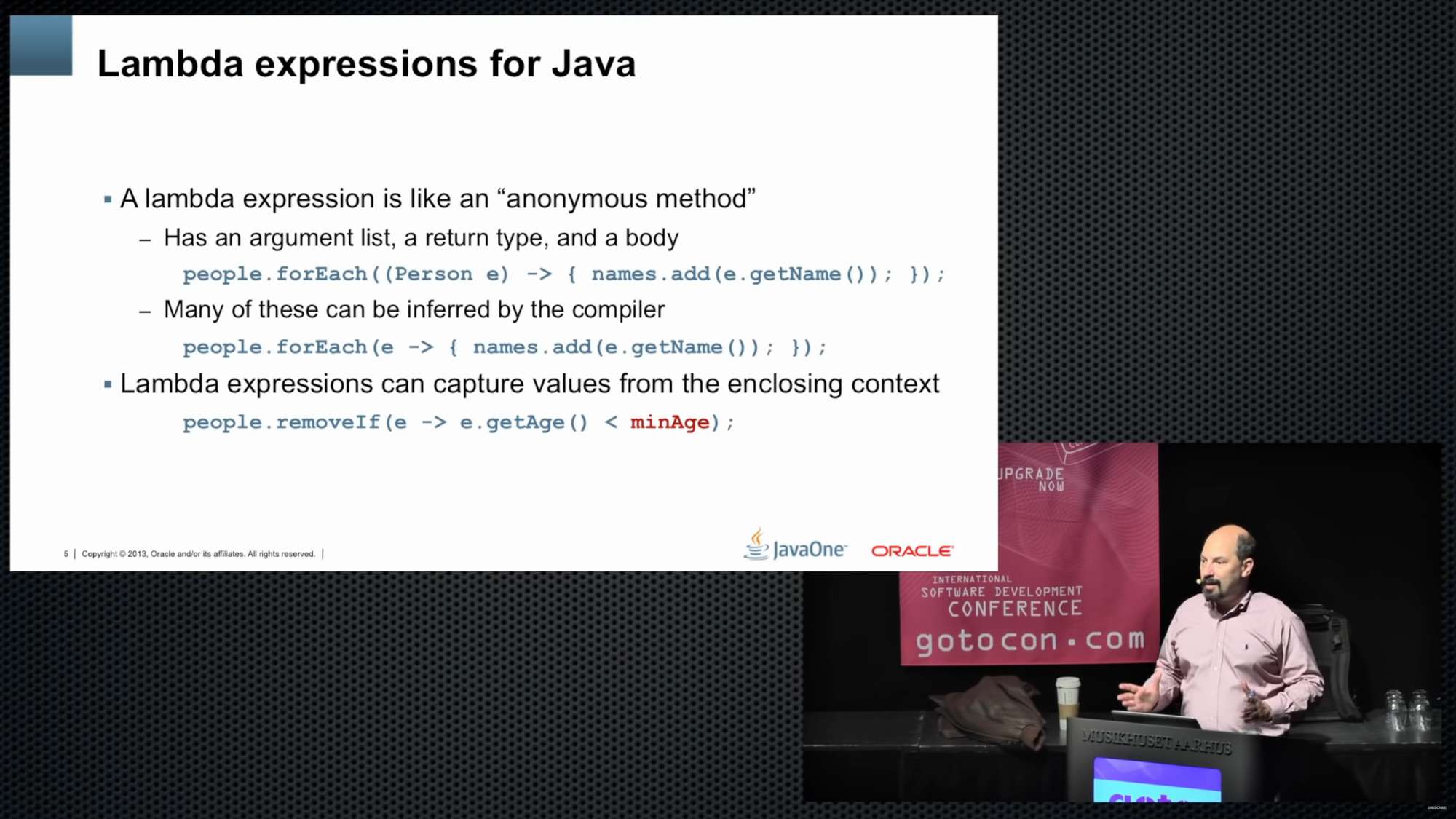

On a single slide, Goetz explains what lambda expressions are and how they look in Java 8. Now, 13 months later, everybody knows them, so there is no reason to repeat that introduction. He then goes on to quickly answer why lambdas were included in the language.

An important reason is parallelization. When it comes to multi-threaded processing of collections, it is best to have the collection provide a customized parallel iteration mechanism instead of letting the user implement one. This is called internal iteration and the opposite of external iteration, e.g. with for loops. If the collection does the iteration itself, it needs to delegate the processing of the individual elements to a function provided by the user. This makes it necessary to have a concise format in which the user can specify such functions. While anonymous classes are a possibility, their syntax is too lengthy for frequent use.

The importance of lambda expressions can be judged by the fact that Java was the last mainstream OO language without them.

▚Type

The first big question the expert group had to answer was what type the new lambda expressions were going to have.

▚Why Not Just Add Function Types?

A seemingly straight forward way to implement lambdas would be to define a the new type. So in addition to primitives, arrays, classes and interfaces there would also be a function type. This immediately entails the question of how this could be implemented in the virtual machine.

One approach would be to represent all functions as a single type and use generics to distinguish them. This would unavoidably bring the "pain of generics" to functions. Type erasure would make it impossible to overload the same method with different function arguments (say with one from string to integer and with another from string to boolean). Generics would also require to box all primitives which would be detrimental to performance.

Goetz then states that due to the many changes to the virtual machine "teaching [it] about 'real' function types would be a huge effort". It would introduce complexity and corner cases and many interoperability challenges between libraries using functions and those not using them.

▚Functional Interfaces

A quick historical detour shows that Java already models functions in many places.

It uses interfaces with only one method to do so.

Prime examples are Runnable, Callable and Comparator.

So instead of adding a new type for functions, the expert group decided to formalize the existing pattern. They named the concept of an interface with a single abstract method functional interface.

The compiler would then be able to interpret all interfaces with one method as a function.

(E.g. Comparator as a generic function from a pair of instances of some typeT to int.)

When a lambda expression is used in a place where such an interface is expected, the compiler can transform the lambda expression to an instance of that interface.

An important bonus of that decision is that old libraries are forward compatible with lambdas! Code that was written before Java 8, which might use interfaces with just one method, can now be used with lambdas. This considerably reduces the amount of necessary rework of existing code.

▚Runtime Representation

Another question is how to represent lambda expressions at runtime, i.e. in byte code. It is important to notice that whatever representation is chosen will be fixed forever.

▚Why Not Just Use Inner Classes?

An obvious approach to the representation of lambdas would be to silently create a matching inner class. This is exactly what anonymous classes do. This has the advantage of being comparatively simple and straight forward. It introduces no new concepts and seamlessly integrates with existing mechanisms.

But it also brings the disadvantages of anonymous classes to lambda expressions. While most of them are largely invisible to the average programmer they also include a suboptimal performance. Or in Goetz's words:

Well, inner classes suck!

▚Why Not Just Use Method Handles?

Goetz then covers method handles. This is a lower level language construct with I am not familiar with. So instead of relating wrong information I'm not going to cover it.

What it comes down to is that method handles also turn out to be no good representation of lambdas. He describes the root cause as follows:

It takes an implementation technique and it conflates our binary representation with that choice of implementation technique.

▚More Indirection!

With the most obvious possibilities failing to properly represent lambdas, the expert group looked for a more indirect approach. One which does not bind the representation to a specific implementation and does not compromise on performance.

So instead of choosing a byte code representation which imperatively creates an interface from a lambda, the byte code merely gives a declarative recipe. It is then up to the runtime to execute that recipe in the best and most performant way.

▚A Recipe For Lambdas

But how could a byte code representation of such a deferred creation look like? It turned out that a tool introduced in Java 7 provides much of the needed functionality.

▚invokedynamic

Prior to Java 7 there were four byte codes for method invocations. These codes are close representations of use cases needed by the Java language:

- calling a static method (invokestatic)

- calling a class method (invokevirtual)

- calling an interface method (invokeinterface)

- everything else (invokespecial, e.g. for constructors)

With the rise of dynamic JVM based languages a new type was needed for cases where an instance's type is not known at compile time. It was eventually introduced in Java 7: invokedynamic. It allows languages to influence the calling behavior of the JVM at runtime. This is done by providing their own specific logic.

It is implemented such that the virtual machine calls back to the language logic when encountering an invokedynamic call site for the first time. The language logic then returns how to resolve that call.

This bootstrap method is a comparatively expensive operation. To avoid calling it every time, the language logic also returns the conditions under which the decision can be reused. The JVM can then optimize invokedynamic call sites as any other invocation byte code which guarantees a comparable performance.

▚Lambda Factory

With invokedynamic at hand, it is fairly straight forward to represent a lambda capture site (i.e. the place where a lambda is used).

First, a method is created which is equivalent to the lambda expression (this is called "desugaring"). Depending on the captured context (e.g. method calls or accessed fields) this can either be an instance or a static method of the class where the expression occurred. A handle to that method is a central ingredient in the recipe for that lambda expression. Other ingredients are the target interface, some metadata (e.g. for serialization) and the values captured by the lambda expression. Returning an interface implementation for such a recipe is called transformation and different strategies exist (e.g. inner classes as described above).

The capture site itself then becomes a factory which takes the recipe for the lambda and returns an implementation of the corresponding functional interface. The factory is represented by a call to invokedynamic with the recipe as an argument.

▚Lambda Metafactory

The bootstrapping process of such an invokedynamic call is realized by the lambda metafactory. Its task is to transform a given recipe to an interface implementation. To this end, it can choose whatever strategy it deems best.

▚Evaluation

Using invokedynamic to represent a lambda capture site as a lambda factory is described by Goetz as "the ultimate procrastination aid". It defers choosing a transformation strategy (from lambda expression to interface implementation) to runtime and makes it a pure implementation detail.

▚Advantages

One advantage is that the runtime has more information about the running program and the underlying system than the compiler. It can thus make a more informed decision about what the best strategy is. It is even possible for different VMs on different systems to provide different transformation strategies, which are optimized to use system specific features.

Another advantage is that changes to the lambda metafactory can happen at any time and all existing code would automatically profit from that without having to be recompiled. So new strategies could be implemented and the mechanism which picks a strategy for a given call site can be improved as well. All this can be done in any minor Java update as it happens behind the scenes.

This mechanism also brings concrete performance advantages with it:

- There is no need for additional fields or static initialization.

So there is no increase in memory or runtime footprint of a class.

- Lambdas which capture no variables only need to be instantiated once.

- Initialization cost is deferred to a lambda's first use, which implies no such costs when one is not used at all.

Last but not least, the implemented mechanism can be used by all JVM based languages. This means that they will also benefit from future optimizations.

▚Performance

But does the indirection have a performance price? Goetz breaks the costs down into three components: linkage, capture and invocation cost. Linkage happens once for each lambda expression and provides the VM with the means to process the expression. Capturing means providing an instance of the functional interface which the lambda expression is implementing. Finally invocation means actually calling the method.

If inner classes were used for lambda expressions, these costs were the following: Linkage means going to the file system to load the byte code for the class. For capture, the loaded class has to be instantiated. The invocation is a regular method call.

For the chosen implementation the costs are as follows: Linkage is the call to the lambda metafactory. It returns a class and for lambdas which use variables from the surrounding scope a new instance has to be created for each capture of the expression. If, on the other hand, an expression uses only variables provided to it as arguments (which is fairly common), the same instance can be reused so there is no capture cost. Finally the invocation is also a regular method call.

To compare these costs, Goetz presents some measurements. The very short and overly simplified summary is this:

- Linkage: Lamdas are between 8% and 24% faster

- Capture: Very similar for inner classes and lambdas which capture no variables.

Non-capturing lambdas, where the same instance can be reused, are somewhat faster on a single thread but really excel in a multi-threaded scenario.

Goetz stresses the fact that this is just "the dumb strategy" and that future optimizations can improve performance even more. He goes on to name how some improvements of the VM could speed lambda processing up.

▚Summary

After a quick dive into the additional requirements for serialization, Goetz summarizes his talk.

Noteworthy is his notion of "obvious-but-wrong" ideas. They seem to be a perfect match but closer inspection might reveal serious problems. Examples of this are the approaches described above. He stresses that one should always be on the lookout for these ideas.

▚Reflection

We saw why Java 8 has no function type but reuses regular interfaces which match a certain condition. We then went to in see how invokedynamic is used to defer the transformation of a lambda expression to an instance of that interface from compile time to runtime. An overview over advantages and performance properties of the chose approach justifies that decision.