JUnit 5 is pretty impressive, particularly when you look under the covers, at the extension model and the architecture. But on the surface, where tests are written, the development is more evolutionary than revolutionary - are there no killer features over JUnit 4? Oh, there are, and today we're gonna investigate the deadliest: parameterized tests.

JUnit 5 has native support for parameterizing test methods as well as an extension point that allows third-party variants of the same theme. In this post we'll look at how to write parameterized tests - creating an extension will be left for the future.

Throughout this post I will use the terms parameter and argument quite a lot and in a way that do not mean the same thing. As per Wikipedia:

The term parameter is often used to refer to the variable as found in the function definition, while argument refers to the actual input passed.

▚Hello, Parameterized World

Getting started with parameterized tests is pretty easy, but before the fun can begin you have to add the following dependency to your project:

- Group ID: org.junit.jupiter

- Artifact ID: junit-jupiter-params

- Version: 5.2.0

- Scope: test

Then start by declaring a test method with parameters and slap on @ParameterizedTest instead of @Test:

@ParameterizedTest

// something's missing - where does `word` come from?

void parameterizedTest(String word) {

assertNotNull(word);

}It looks incomplete - how would JUnit know which arguments the parameter word should take?

And indeed, Jupiter does not execute the test and instead throw a PreconditionViolationException:

Configuration error: You must provide at least

one argument for this @ParameterizedTestSo to make something happen, you need to provide arguments, for which you have various sources to pick from.

Arguably the easiest is @ValueSource:

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(strings = { "Hello", "JUnit" })

void withValueSource(String word) {

assertNotNull(word);

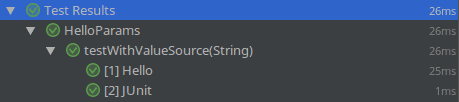

}Indeed, now the test gets executed twice: once word is "Hello", once it is "JUnit".

In IntelliJ that looks as follows:

And that is already all you need to start experimenting with parameterized tests!

For real-life use you should know a few more things, though, about the ins and outs of @ParamterizedTest (for example, how to name them), the other argument sources (including how to create your own), and about something called argument converters.

We'll look into all of that now.

▚Ins And Outs of Parameterized Tests

Creating tests with @ParameterizedTests is straight-forward but there are a few details that are good to know to get the most out of the feature.

▚Test Name

As you can tell by the IntelliJ screenshot above, the parameterized test method appears as a test container with a child node for each invocation.

Those nodes' names default to "[{index}] {arguments}" but a different one can be set with @ParameterizedTest:

@ParameterizedTest(name = "run #{index} with [{arguments}]")

@ValueSource(strings = { "Hello", "JUnit" })

void withValueSource(String word) { }An arbitrary string can be used for the tests' names as long as it is not empty after trimming. The following placeholders are available:

{index}: invocations of the test method are counted, starting at 1; this placeholder gets replaced with the current invocation's index{arguments}: gets replaced with{0}, {1}, ... {n}for the method'snparameters (so far we have only seen methods with one parameter){i}: gets replaced by the argument thei-th parameter has in the current invocation

We'll be coming to alternative sources in a minute, so ignore the details of @CsvSource for now.

Just have a look at the great test names that can be built this way, particularly together with @DisplayName:

@DisplayName("Roman numeral")

@ParameterizedTest(name = "\"{0}\" should be {1}")

@CsvSource({ "I, 1", "II, 2", "V, 5"})

void withNiceName(String word, int number) { }

▚Lifecycle Integration

Parameterized tests are fully integrated into the test lifecycle: Methods annotated with @BeforeEach and @AfterEach are called for each invocation, other extensions like those that resolve more parameters (see below) work as usual, and parameterized tests can be freely mixed with other kinds, be they regular, dynamic, nested, or whatever else will come up in the future.

Parameterized tests are fully integrated into the test lifecycle

▚Non-Parameterized Parameters

Regardless of parameterized tests, JUnit Jupiter already allows injecting parameters into test methods. This works in conjunction with parameterized tests as long as the parameters that vary per invocation come first:

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(strings = { "Hello", "JUnit" })

void withOtherParams(String word, TestInfo info, TestReporter reporter) {

reporter.publishEntry(info.getDisplayName(), "Word: " + word);

}Just as before, this method gets called twice and both times parameter resolvers have to provide instances of TestInfo and TestReporter.

In this case those providers are built into Jupiter but custom providers, e.g. for mocks, would work just as well.

▚Meta Annotations

Last but not least, @ParameterizedTest (as well as all the sources) can be used as meta-annotations to create custom extensions and annotations:

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@ParameterizedTest(name = "Elaborate name listing all {arguments}")

@ValueSource(strings = { "Hello", "JUnit" })

public @interface Params { }

@Params

void testMetaAnnotation(String s) { }▚Argument Sources

Three ingredients make a parameterized test:

Three ingredients make a parameterized test

- a method with parameters

- the

@ParameterizedTestannotation - parameter values i.e.

arguments

Arguments are provided by sources and you can use as many as you want for a test method but need at least one or you get the aforementioned PreconditionViolationException.

A few specific sources exist but you are free to create your own.

The core concepts to understand are:

- each source must provide arguments for all test method parameters (so there can't be one source for the first and another for the second parameter)

- the test is executed once for each group of arguments

▚Value Source

You have already seen @ValueSource in action.

It is pretty simple to use and type safe for a few basic types.

You just add the annotation and then pick from one (and only one) of the following elements:

String[] strings()int[] ints()long[] longs()double[] doubles()

Earlier, I showed that for strings - here you go for longs:

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(longs = { 42, 63 })

void withValueSource(long number) { }There are two main drawbacks:

- due to Java's limitation on valid element types, it can not be used to provide arbitrary objects (although there is a remedy for that - wait until you read about argument converters)

- it can only be used on test methods that have a single parameter

So for most non-trivial use cases you will have to use one of the other sources.

▚Enum Source

This is a pretty specific source that you can use to run a test once for each value of an enum or a subset thereof:

@ParameterizedTest

@EnumSource(TimeUnit.class)

void withAllEnumValues(TimeUnit unit) {

// executed once for each time unit

}

@ParameterizedTest

@EnumSource(

value = TimeUnit.class,

names = {"NANOSECONDS", "MICROSECONDS"})

void withSomeEnumValues(TimeUnit unit) {

// executed once for TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS

// and once for TimeUnit.MICROSECONDS

}Straight forward, right?

But note that @EnumSource only creates arguments for one parameter and so it can only be used on single-parameter methods.

By the way, if you need more detailed control over which enum values are provided, take a look at @EnumSource's mode attribute.

▚Method Source

@ValueSource and @EnumSource are pretty simple and somewhat limited - on the opposite end of the generality spectrum sits @MethodSource.

It simply names the methods that will be called to provide streams of arguments.

Literally:

@ParameterizedTest

@MethodSource("createWordsWithLength")

void withMethodSource(String word, int length) { }

private static Stream<Arguments> createWordsWithLength() {

return Stream.of(

Arguments.of("Hello", 5),

Arguments.of("JUnit 5", 7));

}Arguments is a simple interface wrapping an array of objects and Arguments.of(Object... args) creates an instance of it from the specified varargs.

The class backing the annotation does the rest and withMethodSource gets executed twice: Once with word = "Hello" / length = 5 and once with word = "JUnit 5" / length = 7.

If the source is only used for a single argument, it may blankly return such instances without wrapping them into Arguments:

@ParameterizedTest

@MethodSource("createWords")

void withMethodSource(String word) { }

private static Stream<String> createWords() {

return Stream.of("Hello", "Junit");

}The method called by @MethodSource must return a kind of collection, which can be any Stream (including the primitive specializations), Iterable, Iterator, or array.

It must be static, can be private, and doesn't have to be in the same class: @MethodSource("org.codefx.Words#provide") works, too.

If no name is given to @MethodSource, it will look for an arguments-providing method with the same name as the parameterized test method.

I do not recommend relying on this, though, because it obfuscates where arguments come from and leads to unsuitable method names - testing something and providing values shouldnt' have the same name.

So as you can see, @MethodSource is a very generic source of arguments.

But it incurs the overhead of declaring a method and putting together the arguments, which is a little much for simpler cases.

These can best be served with the two CSV sources.

▚CSV Sources

Now it gets really interesting.

Wouldn't it be nice to be able to define a handful of argument sets for a few parameters right then and there without having to go through declaring a method?

Enter @CsvSource!

With it you declare the arguments for each invocation as a comma-separated list of strings and leave the rest to JUnit:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({ "Hello, 5", "JUnit 5, 7", "'Hello, JUnit 5!', 15" })

void withCsvSource(String word, int length) { }In this example, the source is given three strings, which it identifies as three groups of arguments, leading to three test invocations.

It then goes ahead to take them apart on commas and convert them to the target types.

See the single quotes in "'Hello, JUnit 5!', 15"?

That's the way to use commas without the string getting cut in two at that position.

That all arguments are represented as strings begs the question of how they are converted to the proper types. We'll turn to that in a minute but before we do, I want to quickly point out that if you have large sets of input data, you are free to store them in an external file:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvFileSource(resources = "/word-lengths.csv")

void withCsvSource(String word, int length) { }Note that resources can accept more than one file name and processes them one after another.

The other attributes of @CsvFileSource allow to specify the file's encoding, line separator, and delimiter.

▚Custom Argument Sources

If the sources built into JUnit do not fulfill all of your use cases, you are free to create your own. I won't go into many details - suffice it to say, you have to implement this interface...

public interface ArgumentsProvider {

Stream<? extends Arguments> provideArguments(

ContainerExtensionContext context) throws Exception;

}... with a class that has a parameterless constructor (if it's a nested class, remember to make it static) and then use it with @ArgumentsSource(MySource.class) or a custom annotation.

You can use the extension context to access various information, for example the method the source is called on so you know how many parameters it has.

Now, off to converting those arguments!

▚Argument Converters

With the exception of method sources, argument sources have a pretty limited repertoire of types to offer: just strings, enums, and a few primitives. This does of course not suffice to write encompassing tests, so a road into a richer type landscape is needed. Argument converters are that road:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({ "(0/0), 0", "(0/1), 1", "(1/1), 1.414" })

void convertPointNorm(@ConvertPoint Point point, double norm) { }Let's see how to get there...

First, a general observation: No matter what types the provided argument and the target parameter have, a converter is always asked to convert from one to the other. Only the previous example declared a converter, though, so what happened in all the other cases?

▚Default Converter

Jupiter provides a default converter that is used if no other was registered.

If argument and parameter types match, conversion is a no-op but if the argument is a String it can be converted to a number of target types - here are most of them:

charorCharacterif the string has length 1 (which can trip you up if you use UTF-32 characters like smileys because they consist of two Javachars)- all of the other primitives and their wrapper types with their respective

valueOfmethods - any enum by calling

Enum::valueOfwith the string and the target enum - a bunch of temporal types like

Instant,LocalDateTimeet al.,OffsetDateTimeet al.,ZonedDateTime,Year, andYearMonthwith their respectiveparsemethods (strings have to be ISO 8601 or a conversion pattern has to be defined - see below) FilewithFile::newandPathwithPaths::get

Here's an example that shows some of them in action:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({"true, 3.14159265359, AUGUST, 2018, 2018-08-23T22:00:00"})

void testDefaultConverters(

boolean b, double d, Summer s, Year y, LocalDateTime dt) { }

enum Summer {

JUNE, JULY, AUGUST, SEPTEMBER;

}If your dates don't come in ISO 8601, @JavaTimeConversionPattern helps you out:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({"true, 3.14159265359, AUGUST, 2018, 23.08.2018"})

void testDefaultConverters(

boolean b, double d, Summer s, Year y,

@JavaTimeConversionPattern("dd.MM.yyyy") LocalDate dt) { }It is likely that the list of supported types grows over time but it is obvious that it can not include those specific to your code base. This is where factories and custom converters enter the picture.

▚Object Factories

Many of the conversions above have something in common: They take the given String and pass it to a static factory method on the target type, for example to this method on Instant:

public static Instant parse(CharSequence text) { /*...*/ }This pattern is actually pretty common and JUnit supports it out of the box:

- If a type has a single non-private, static method that accepts a

Stringand returns an instance of itself, Jupiter uses this factory method to convert strings to instances. - If there are zero or more than one factory methods, Jupiter settles for a factory constructor, which must be non-private and accept a

String.

As an example, let's use a custom Point class that has a static factory method from, which accepts strings of the form "(x/y)".

Then this works without further code on our end:

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(strings = { "(0/0)", "(0/1)","(1/1)" })

void convertPoint(Point point) { }What if you're stuck with a class that doesn't have a factory, though, or whose factory does not suit your needs? Then you're gonna have to write a converter.

▚Custom Converters

Custom converters allow you to convert the arguments a source emits (often strings) to instances of the arbitrary types that you want to use in your tests.

Creating them is a breeze - all you need to do is implement the ArgumentConverter interface:

public interface ArgumentConverter {

Object convert(

Object input, ParameterContext context)

throws ArgumentConversionException;

}It's a little jarring that input and output are untyped but due to erasure there's no good way to fix that. You can use the parameter context to get more information about the parameter you are providing an argument for, e.g. its type or the instance to which the test belongs.

For the Point class, which already has a static factory method, we wouldn't actually need a converter, but we'll create one anyway to try it out.

It's as simple as this:

@Override

public Object convert(

Object input, ParameterContext parameterContext)

throws ArgumentConversionException {

if (input instanceof Point)

return input;

if (input instanceof String)

try {

return Point.from((String) input);

} catch (NumberFormatException ex) {

String message = input

+ " is no correct string representation of a point.";

throw new ArgumentConversionException(message, ex);

}

throw new ArgumentConversionException(input + " is no valid point");

}The first check input instanceof Point is a little asinine (why would it already be a point?) but once I started switching on type I couldn't bring myself to ignoring that case.

Feel free to judge me.

Now you can register the converter with @ConvertWith:

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(strings = { "(0/0)", "(0/1)","(1/1)" })

void convertPoint(@ConvertWith(PointConverter.class) Point point) { }Or you can create a custom annotation to make it look less technical:

@Target({ ElementType.ANNOTATION_TYPE, ElementType.PARAMETER })

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@ConvertWith(PointConverter.class)

public @interface ConvertPoint { }

@ParameterizedTest

@ValueSource(strings = { "(0/0)", "(0/1)","(1/1)" })

void convertPoint(@ConvertPoint Point point) { }This means, by annotating a parameter with either @ConvertWith or your custom annotation, JUnit Jupiter passes whatever argument a source provided to your converter.

You will usually register this with sources that emit strings, like @ValueSource or @CsvSource, so you can then parse them into an object of your choice.

▚Argument Accessors And Aggregators

Sometimes, an argument source is no good fit for your parameterized method. As an example, consider the case where some external process generates a CSV file that you want to use in our tests. If that file has way more columns than your test actually needs, you would end up with a ridiculous number of unused parameters, just to align with the file's format. Not good.

The source may also split input for an argument conversion across several columns, so instead of storing points as "(x/y)", the coordinates could come in two columns, which Jupiter, by default, maps to two parameters.

ArgumentsAccessor and ArgumentsAggregator to the rescue!

This post is already long enough and I'm not going into details on these - instead I'll leave you with links to their Javadoc (accessor, aggregator) and a small example for each:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({ "0, 0, 0", "1, 0, 1", "1.414, 1, 1" })

void testPointNorm(double norm, ArgumentsAccessor arguments) {

Point point = Point.from(

arguments.getDouble(1), arguments.getDouble(2));

/*...*/

}

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({ "0, 0, 0", "1, 0, 1", "1.414, 1, 1" })

void testPointNorm(

double norm,

@AggregateWith(PointAggregator.class) Point point) {

/*...*/

}

static class PointAggregator implements ArgumentsAggregator {

@Override

public Object aggregateArguments(

ArgumentsAccessor arguments, ParameterContext context)

throws ArgumentsAggregationException {

return Point.from(

arguments.getDouble(1), arguments.getDouble(2));

}

}No wait, one more tip: If a source provides more arguments than you have parameters, that's not a problem.

Except when you also need non-parameterized arguments because they must come last and would clash with the parameterized ones, leading to a ParameterResolutionException.

You can make that work, by injecting an ArgumentsAccessor into the mix - it eats up the superfluous arguments:

@ParameterizedTest

@CsvSource({ "0, 0, 0", "1, 0, 1", "1.414, 1, 1" })

// without ArgumentsAccessor in there,

// this leads to a ParameterResolutionException

void testEatingArguments(

double norm,

ArgumentsAccessor arguments,

TestReporter reporter) {

/*...*/

}▚Reflection

That was quite a ride, so let's make sure we got everything:

- We started by adding the junit-jupiter-params artifact as a dependency and putting

@ParameterizedTeston test methods with parameters.

After looking into how to name parameterized tests we discussed where the arguments come from.

- The first step is to use a source like

@ValueSource,@MethodSource, or@CsvSourceto create groups of arguments for the method.

Each group must have arguments for all parameters (except those left to parameter resolvers) and the method will be invoked once per group.

It is possible to implement custom sources and register them with @ArgumentsSource.

- Because sources are often limited to a few basic types, the second step is to convert them to arbitrary ones.

The default converter does that for primitives, enums, some core types like date/time or files, and all classes that have a suitable factory; custom converters can be applied with @ConvertWith.

This allows you to easily parameterize your tests with JUnit Jupiter!

It is entirely possible, though, that this specific mechanism does not fulfill all of your needs. In that case you will be happy to hear that it was implemented via an extension point that you can use to create your own variant of parameterized tests - I will look into that in a future post, so stay tuned.