JUnit 5 has a very interesting architecture. First of all, the project is split into three sub-projects: Jupiter, Vintage, and Platform. They communicate via published APIs, which allows tools and libraries to inject customized behavior. Then, each sub-project is split into several artifacts to separate concerns and guarantee maintainability. In this post we'll explore the architecture itself as well as the reasons behind it.

▚JUnit 4

Ignoring Hamcrest, JUnit 4 has no dependencies and bundles all functionality in one artifact. This is in stark violation of the single responsibility principle and it shows: developers, IDEs, build-tools, other testing frameworks, extensions; they all depend on the same artifact.

Among this group, regular developers are, for once, the unobtrusive ones. They usually rely on JUnit's public API and that's that.

But other testing frameworks and extensions and especially IDEs and build tools are a different breed. They reach deep into JUnit's innards. Non-public classes, internal APIs, even private fields are not safe. This way they end up depending on implementation details, which means that the JUnit maintainers can not easily change them when they want to, thus hindering further development. With the words of Johannes Link, one of JUnit 5's initiators:

The success of JUnit as a platform prevents the development of JUnit as a tool.

Of course those tools' developers did not do this out of spite. To implement all the shiny features that we value so much they had to use internals because JUnit 4 does not have a rich enough API to fulfill their requirements.

The JUnit 5 team set out to make things better...

▚JUnit 5

▚Separating Concerns

Taking a step back it is easy to identify at least two separate concerns:

- an API to write tests against

- a mechanism to discover and run tests

Looking at the second point a little closer we might ask "Which tests?".

Well, JUnit tests, of course.

"Yes but which version?" Err... "And what kinds of tests?" Wait, let me... "Just the lame old @Test-annotated methods?

What about fancy new ways to run tests?" Ok, ok, shut up already!

To decouple the concrete variant of tests from the concern of running them, the second point got split up:

- an API two write tests against

- a mechanism to discover and run tests

- a mechanism to discover and run a specific variant of tests

- a mechanism to orchestrate the specific mechanisms

- an API between them

▚Splitting JUnit 5

With the concerns sorted out, "JUnit the tool" (which we use to write tests) and "JUnit the platform" (which tools use to run our tests) can be clearly separated. To drive the point home, the JUnit team decided to split JUnit 5 into three sub-projects:

"JUnit the tool" and "JUnit the platform" are clearly separated

- JUnit Jupiter:

The API against which we write tests (addresses concern 1.) and the engine that understands it (2a.).

- JUnit Vintage:

Implements an engine that allows to run tests written in JUnit 3 and 4 with JUnit 5 (2a.).

- JUnit Platform:

Contains the engine API (2c.) and provides a uniform API to tools, so they can run tests (2b.).

So when I've presented the basics and talked about "JUnit 5's new API", I was lying, even if just a little. I actually explained JUnit Jupiter's API.

▚Architecture

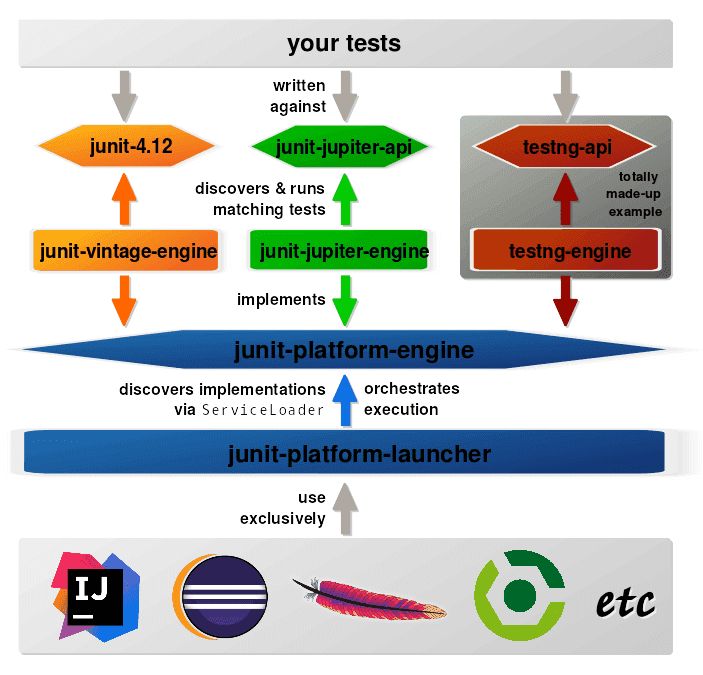

JUnit 5's architecture is the result of that distinction. These are some of its artifacts:

- junit-jupiter-api (1):

The API against which developers write tests. Contains all the annotations, assertions, etc. that we saw when we discussed JUnit 5's basics.

- junit-jupiter-engine (2a):

An implementation of the junit-platform-engine API that runs JUnit 5 tests.

- junit-vintage-engine (2a):

An implementation of the junit-platform-engine API that runs tests written with JUnit 3 or 4. Here, the JUnit 4 artifact junit-4.12 acts as the API the developer implements her tests against (1) but also contains the main functionality of how to run the tests. The engine could be seen as an adapter of JUnit 3/4 for version 5.

- junit-platform-engine (2c):

The API all test engines have to implement, so they are accessible in a uniform way. Engines might run typical JUnit tests but alternatively implementations could run tests written with TestNG, Spock, Cucumber, etc.

- junit-platform-launcher (2b):

Uses the ServiceLoader to discover test engine implementations and to orchestrate their execution.

It provides an API to IDEs and build tools so they can interact with test execution, e.g. by launching individual tests and showing their results.

Makes sense, right?

Most of that structure is hidden from us front-line developers. Our projects only need a test dependency on the API and engine we are using; everything else comes with our tools.

▚API Lifecycle

Now, about those internal APIs everybody was using. The team wanted to solve this problem as well and created a lifecycle for its API. Here it is, with the explanations straight from the source:

Internal:

Must not be used by any external code. Might be removed without prior notice.

Deprecated:

Should no longer be used, might disappear in the next minor release.

Experimental:

Intended for new, experimental features where the publisher of the API is looking for feedback. Use with caution. Might be promoted to Maintained or Stable in the future, but might also be removed without prior notice.

Maintained:

Intended for features that will not be changed in a backwards-incompatible way for at least the next minor release of the current major version. If scheduled for removal, such a feature will be demoted to Deprecated first.

Stable:

Intended for features that will not be changed in a backwards-incompatible way in the current major version.

Publicly visible classes are annotated with with @API(usage) where usage is one of these values.

(I wonder whether @API should be annotated with @API.

😂) This, so the plan goes, gives API callers a better perception of what they're getting into and the team the freedom to mercilessly change or remove unsupported APIs.

To quickly figure out which APIs are experimental, have the a look at the user guide, which has a section on that.

By the way, if you'd like to use this annotation in your own project, you can do that easily. It is maintained in a separate project and published under org.apiguardian : apiguardian-api, current version 1.0.0.

▚Open Test Alliance

There's one more thing, though. The JUnit 5 architecture enables IDEs and build tools to use it as a facade for all kinds of testing frameworks (assuming those provide corresponding engines). This way tools would not have to implement framework-specific support but can uniformly discover, execute, and assess tests.

Or can they?

Test failures are typically expressed with exceptions but different test frameworks and assertion libraries do not share a common set.

Instead, most implement their own variants (usually extending AssertionError or RuntimeException), which makes interoperability more complex than necessary and prevents uniform handling by tools.

To solve this problem the JUnit team split off a separate project, the Open Test Alliance for the JVM. This is their proposal:

Based on discussions with IDE and build tool developers from Eclipse, Gradle, and IntelliJ, the JUnit 5 team is working on a proposal for an open source project to provide a minimal common foundation for testing libraries on the JVM.

The primary goal of the project is to enable testing frameworks like JUnit, TestNG, Spock, etc.

and third-party assertion libraries like Hamcrest, AssertJ, etc. to use a common set of exceptions that IDEs and build tools can support in a consistent manner across all testing scenarios - for example, for consistent handling of failed assertions and failed assumptions as well as visualization of test execution in IDEs and reports.

Up to now the mentioned projects' response was underwhelming, i.e. mostly lacking. If you think this is a good idea, you could support it by bringing it up with the maintainers of your framework of choice.

▚New Generation Of Testing

All the work that went into JUnit 5's architecture and particularly the decision to provide a stable API for test engines follows one goal: To make the success of JUnit as a platform available to other testing frameworks.

JUnit 4 has had stellar tool support and IDE and build tool developers are making the same true for JUnit 5. But with the new version, the JUnit project is no longer the only one benefiting from that support! All that other testing frameworks need to do to get the same kind of support is to implement an engine for their framework that adheres to the API defined in junit-platform-engine. Then, bahm!, Maven can run them, Gradle can, and so can Eclipse, IntelliJ, and every other tool that has native support for JUnit 5.

This is huge! Traditionally, new testing frameworks had to fight an uphill battle, where adoption was difficult without support by a developer's everyday tools but that support had to be implemented and maintained for each tool and by the project itself. Now the tables have turned! Given a good idea all a project has to do is implement an engine and everybody can start experimenting in their favorite IDE with the same kind of support JUnit gets.

All a project has to do for great tool support is implement an engine

With the effort that is required to get a new idea for a testing framework out into the wild reduced considerably and with the ease of experimentation significantly improved, we may see a surge of new ideas. This, in my opinion, heralds a new generation of testing on the JVM.

And it already shows - here are some community engines that were developed over the last year:

- jqwik: "a simpler JUnit test engine"

- Specsy: "a BDD-style unit-level testing framework"

- Spek: "a Kotlin specification framework for the JVM"

- brahms: "Test engine ideas"

▚Reflection

We have seen how the JUnit 5 architecture divides the API for writing tests and the engines for running them into separate parts, splitting the engines further into an API, a launcher using it, and implementations for different test frameworks. This gives users lean artifacts to develop tests against (because they only contain the APIs), testing frameworks only have to implement an engine for their API (because the rest is handled by JUnit), and build tools have a stable launcher to orchestrate test execution.

The ease with which other projects can get top-level support is a boon to experimenting with new ideas and will bring us a new generation of testing frameworks.

The next post in this series about JUnit 5 discusses another architectural gem: its extension model.