▚Intro

Hi everyone,

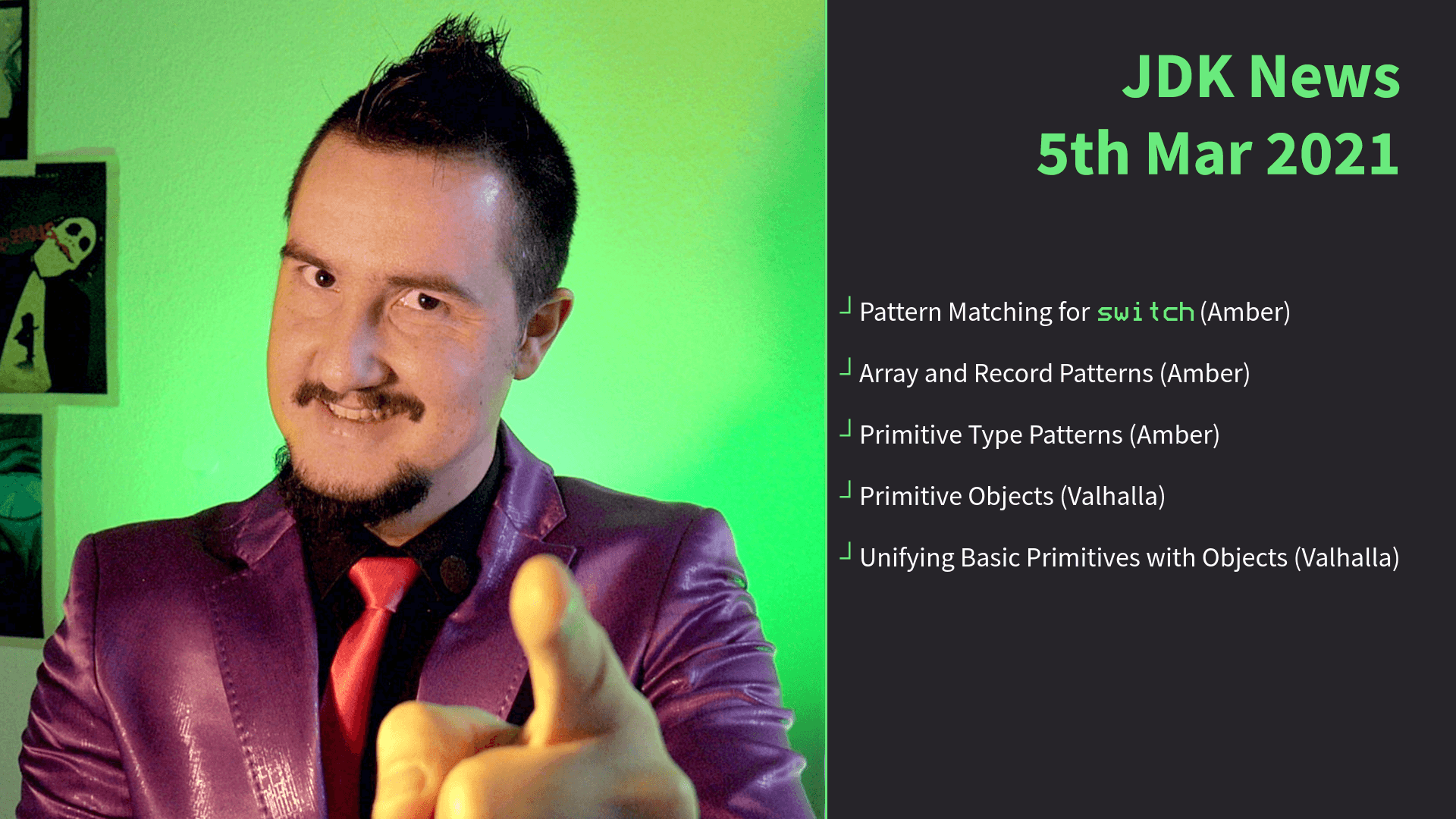

I'm nipafx (but you can call me Nicolai) and today it's gonna be you, me, and the JDK news of the last few weeks up to today, March 5th 2021.

As you know, the JDK is developed out in the open and lots of interesting ideas and considerations are discussed on its many mailing lists. For this episode, I combed through projects Amber and Valhalla and came back with these topics, many of them draft JEPs that were recently made public:

- Pattern Matching for

switch(Amber) - Array and Record Patterns (Amber)

- Primitive Type Patterns (Amber)

- Primitive Objects (Valhalla)

- Unifying Basic Primitives with Objects (Valhalla)

For the next few minutes, keep in mind that we're peeking into an ongoing conversation, so none of this is decided and there's a lot of speculation in there, some of which is mine. Don't get distracted by the syntax - it's often just a straw man - and focus on language capabilities instead. And please take a look at the relevant links before making up your mind - the description down below has a lot of them.

With that out of the way, let's dive right in!

▚Pattern Matching for switch

This one has been on the horizon for quite some time and now we finally see the draft JEP.

The goal is to allow pattern matching in switch expressions and statements.

Here's an example.

It uses type patterns, but the specific kind of pattern doesn't matter - it's just the only one we have so far.

Allow pattern matching in

switch

expressions

String formatterWithPatternSwitch(Object object) {

// statically import String.format

return switch (object) {

case Integer i -> format("int %d", i);

case Byte b -> format("byte %d", b);

case Long l -> format("long %d", l);

case Double d -> format("double %f", d);

case String s -> format("String %s", s);

default -> o.toString();

};

}This has a few essential advantages over the corresponding if-else-chain, even if you use type patterns for that one as well:

- it's more expressive - as the JEP describes, we're saying "the parameter

objectmatches at most one of the following conditions, figure it out and evaluate the corresponding arm" - it's safer because the compiler checks completeness for switch expressions - this should already work with sealed classes

- it's easier to read and write because it's less code

- it's faster because

switchexpressions have constant run time as opposed to the linear run time of anif-else-chain

▚Guard Patterns

It's nice to be able to use a series of simple patterns, but that's not always gonna cut it in real life, where conditions are often more complex.

One way to resolve this would be to give case labels an additional feature that allows evaluating boolean conditions, but there's a more powerful solution out there.

A new kind of pattern

Instead of limiting additional conditions to switch, why not more generally add that feature to pattern matching by creating a new kind of pattern?

These are called guard patterns:

void testShape(Shape shape) {

switch (shape) {

case Triangle triangle

// guard pattern

& true(triangle.calculateArea() > 100) ->

System.out.println("Large triangle");

default ->

System.out.println(

"Any shape (including small triangles)");

}

}If you're interested to learn more about the thought process behind this features, for example the surprising true() construct, check this thread on the mailing list.

▚How to Handle null in Deconstruction Patterns

At the moment, switch is hostile to null and throws a NullPointerException if the switched-over instance is null.

While I appreciate not taking any BS and instead failing fast, this strict approach makes lesser sense the more switch will be used with reference types and non-trivial patterns.

So the JEP proposes a new case label null:

void nullOrString(Object object) {

switch (object) {

case null -> System.out.println("Null");

case String string ->

System.out.println("String: " + string);

}

}It works as follows:

- without

case null,switchcan throw aNullPointerException- this is backwards compatible with current code case null, Type variablecan be used to foldnull-handling into other case- unfortunately,

defaultcan't matchnullbecause of backwards compatibility, socase null, defaultwill be possible

Following this, there was a very interesting discussion that I recommend you check out if you have about half an hour. What I found so enticing was that it once again showed how complicated trade-offs are hiding in the details - this one was regarding consistency.

▚Array Patterns

The second Amber draft JEP dealt with array and record patterns. I don't need to go into details on array patterns because I covered them in the last JDK news. So let's focus on record patterns.

▚Record Patterns

Record patterns deconstruct a record into its components:

record Point(int x, int y) { }

if (object instanceof Point(int x, int y))

System.out.println(x + y);This should be pretty straightforward - you can see that there's a Point record with two components x and y.

The deconstruction pattern looks exactly like the constructor, but works in reverse: if object is indeed a Point, it is taken apart and its component values are assigned to the new variables x and y.

The deconstruction pattern looks exactly like the constructor, but works in reverse

A cool aspect of patterns is that they can be composed or nested:

// tired

if (rect instanceof Rectangle(

ColoredPoint ul, ColoredPoint lr)){

if (ul != null) {

return;

}

Color color = ul.color();

System.out.println(color);

}

// wired

if (rect instanceof Rectangle(

ColoredPoint(Point point, Color color),

ColoredPoint lr)) {

System.out.println(color);

}Here, we not only want to take rect apart, but want to further deconstruct its upper left ColoredPoint into a point and color.

Instead of doing that in two steps, we can nest the ColoredPoint deconstruction pattern in the outer Rectangle pattern.

Here's a more extreme version:

Rectangle rect = // ...

// no

if (rect == null)

return;

ColoredPoint ul = rect.ul();

if (ul == null)

return;

Point ulPoint = ul.point();

if (ulPoint == null)

return;

int ulX = ulPoint.x();

System.out.println("Lower-left Corner: " + ulX);

// yes

if (rect instanceof Rectangle(

ColoredPoint(

Point(var ulX, var ulY),

var color),

var lr))

System.out.println("Lower-left Corner: " + ulX);Definitely takes some getting used to.

If you don't like either solution, just forbid null and it boils down to a two-liner:

// YES

int ulX = rect.ul().point().x();

System.out.println("Lower-left Corner: " + ulX);Better right?

But this only works if we know rect is a Rectangle, its upper left corner point has a method point(), and the returned point has an x() method.

If the involved types are more general (e.g. rect or the return of point() could be a Shape) or the methods may return null, the nested pattern match would address that without being much more cumbersome than the call chain.

Surely way more expressive than the chained checks.

▚Primitive Type Patterns

For now we might as well rename Project Amber to Project Pattern Matching because the last news from it are once again focused on that. This one concerns type patterns for primitives. These are not that powerful because there's neither inheritance nor composition involved.

Initially, you'd think this would be nice:

int anInt = 300;

switch (anInt) {

case byte b: // A ...

case short s: // B ...

case int i: // C ...

}300 can't be a byte, but it can be a short, so branch B?

And here?

Object o = new Short(3);

switch (o) {

case byte b: // A ...

case short s: // B ...

}A Short is a short and yet branch A?

Also, there need to be special rules for each pair of supported primitives - that are dozens.

Brian Goetz called it "an exercise in complexity"

Instead he proposes something like this:

switch (anInt) {

case fromByte(var b): // A ...

case fromShort(var s): // B ...

}"What's fromByte and fromShort?" you might think.

Those are method patterns, but I don't have time to cover these today - I leave a link to their explanation down below as well as to the mail in which Brian explains which benefits they have over the case $primitive approach.

▚Primitive Objects

And that's it for Amber, now let's move over to Valhalla. This project has been running for a long time, but it looks like the exploration was fruitful and after many iterations concrete proposals are coming out in the form of three draft JEPs, two of which were already posted. For now, let's stick to the first one, on primitive objects.

Let's start at the beginning.

In Java, there's a fundamental rift between primitives like int and float and reference types like Object, String, and Integer.

Primitives have better performance:

Project Valhalla brings first concrete proposals

- no indirection (flat memory)

- no header as overhead (dense memory)

- no garbage collection

Reference types, on the other hand, have better abstractions and safety:

- fields, constructors, methods

- access control

- (sub)typing, polymorphism

Reference types also have identity, meaning two equal instances like Integer(5) and Integer(5) may not be identical - a proposition that makes no sense for two occurrences of the int 5.

Identity allows for locking, mutability, and a few other shenanigans.

The problem with this split is that it makes developers choose between performance and abstraction. And not least because we're somewhat prone to prematurely give up the latter for a random chance to increase the former, that's not ideal.

This split makes developers choose between performance and abstraction

▚Enter Primitive Objects

Regular reference types are called identity classes and the instances identity objects.

They implicitly implement the new marker interface IdentityObject.

Opposed to that are the new primitive classes with primitive objects - instances without identity, meaning no mutability and no locking.

They implicitly implement the new marker interface PrimitiveObject.

As the JEP states:

JVMs may freely duplicate and re-encode [primitive objects] in an effort to improve computation time, memory footprint, and garbage collection performance.

Here's what a primitive class looks like:

interface Shape {

boolean contains(Point p);

}

primitive class Point implements Shape {

private double x;

private double y;

public Point(double x, double y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public double x() { return x; }

public double y() { return y; }

public Point translate(double dx, double dy) {

return new Point(x+dx, y+dy);

}

public boolean contains(Point p) {

return equals(p);

}

}Some of the details are:

- primitive classes are implicitly final

- all fields are implicitly final

- no circular dependency on itself

- no

synchronizedmethods

And a few other ones that you'll find in the JEP. But this is not all!

primitive class Point { /*...*/ }

Point p = // primitive value

Point.ref p = // primitive referenceTake a declaration Point p.

This is what's called a primitive value, which is handled without references and headers.

Such a variable can't be null - the default Point.default has all fields set to 0, false, [], null, etc.

Alternatively, you can write Point.ref p to get a primitive reference that follows identity object logic and allows null.

The JEP lists cases where this may be desired, but considers it unnecessary in many programs.

To make matters more complicated but also more compatible, the JEP proposes another kind of primitive classes, called reference-favoring.

Then, Point p is a primitive reference and Point.val p a primitive value.

// reference-favoring primitive class

primitive class Point.val { /*...*/ }

Point.val p = // primitive value

Point p = // primitive referenceWe will see that come into play in the next draft JEP and I assume even more so in the remaining JEP about generic specialization. But before we get there, I want to briefly switch to the mailing list.

▚What about void and Void?

Because there was a great question by Nir Lisker:

Will void and Void benefit from the type system improvements and how do might they relate to one another?

Brian replied:

Adjusting the language to understand that

voidandVoidare related is not hard, allowing us to ignore the need to return a value. [...] Turningvoidinto a proper (unit) type is harder, but ultimately valuable;

There are some challenges on the way, but he doubts "any of these are blockers".

That would be pretty cool because if that goal were to be achieved, many functional interface specializations would become unnecessary.

For example, the interface IntConsumer could be a Consumer<int>, which in turn could be a Function<int, void>.

This would make java.util.functions so much simpler!

IntConsumer

Consumer<int>

Function<int, void>▚Unifying Basic Primitives with Objects

The second, related draft JEP plans to apply these new type system capabilities to the existing primitives and their wrappers in two steps:

First, migrate the eight wrapper classes to be reference-favoring primitive classes.

That means, say, Integer i is no longer a reference because it's an identity object (in the new terminology).

Now it is a reference because it is a primitive reference of a reference-favoring primitive class.

While 99% of use cases should remain untouched by this change, it does make a few subtle differences (that the JEP lists).

More importantly, though, it places these types into a different category than the other reference types, which is arguably where they belong.

1. Migrate wrapper classes to primitive classes

Second, treat the basic primitive values as instances of the migrated wrapper classes and the primitive type keywords as aliases for their primitive value types. This change has more impact than the first one. While it keeps these values "primitive" in the old sense, it nonetheless turns them into instances of a class, which means among other things that they now have methods that you can call!

2. Treat primitive type keywords as aliases for primitive value types

// reference-favoring primitive class

primitive class Integer.val { /*...*/ }

// primitive reference

Integer i = Integer.valueOf(42);

// primitive value Integer.val ~ int

int i = 42;

// primitive values belong to classes

// ~> they have methods! 😲

String s = 42.toString();▚Outro

Finally, as mentioned before, there's a third JEP in the making that will address the crux of the matter around primitive classes: How will generics deal with them?

I can't wait to dig into that proposal! If you don't want to miss it either, subscribe and hit the bell icon, so you get notified. If you like these shorter form news about the development in the JDK, let me know with a like, so there will be more of them.

Until then, have a great time. So long...