I consider Java's module system a big boon for maintainability. That is, if tools, frameworks, and libraries play along, but unfortunately many don't yet, at least not to the degree where they interoperate seamlessly. To classify tools by their level of support, I propose the JPMS Maturity Model laid out in this post. This model gives users a clear indication of how well their tools of choice support the module system and informs maintainers which features they could target next.

As an example, as of August 2019, the newest versions of IntelliJ, Eclipse, and Surefire all run tests of a module differently: From all on the class path (IntelliJ) to initial module and module dependencies on module path, rest on class path (Surefire) to all on module path (Eclipse), you get different behavior in each tool. You would hope that it doesn't matter much where tests are run, but, then again, discrepancies between dev and build environment have the tendency to come back to bite you sooner or later. And let's not even get started on configuring any of this - it's almost exclusively decided behind closed doors. You see, there's room for improvement.

▚Categories And Their Shortcomings

The module system poses widely different challenges for different projects, but, painting with a broad brush, two categories emerge:

- Tools are standalone applications (or plugins thereof) that operate on your code: IDEs, build tools, code analysis tools, etc.

- Dependencies are reusable building blocks that interact with your code: libraries and frameworks.

While tools mostly need to handle module declarations/descriptions and balance class path vs module path, for dependencies the main question is whether they can run as modules and, if necessary, interact with your code as a module. Of course there's a little more to it and we'll see that when we come to the maturity model's levels.

(Nota bene: We could also analyze tools as applications, assessing whether they function on the module path or not, but unless that impacts their feature set, I'm going to ignore it because it doesn't really matter to users.)

The tools-vs-dependencies dichotomy is not clear-cut, though. If you use Maven as a build tool, it falls into the first category, but if you write a plugin for it, it's the second. To further complicate matters, more complex projects have feature sets that need to be assessed individually. IDEs and build tools, for example, may treat compilation and tests differently. Again, take Maven as an example, where these tasks are handled by separate plugins, which hence require their own assessments.

It's not as simple as "$PROJECT supports the module system"

As you can see, it's not as simple as $PROJECT does/doesn't support the module system. We'll see examples of that in the model definitions.

▚JPMS Maturity Model

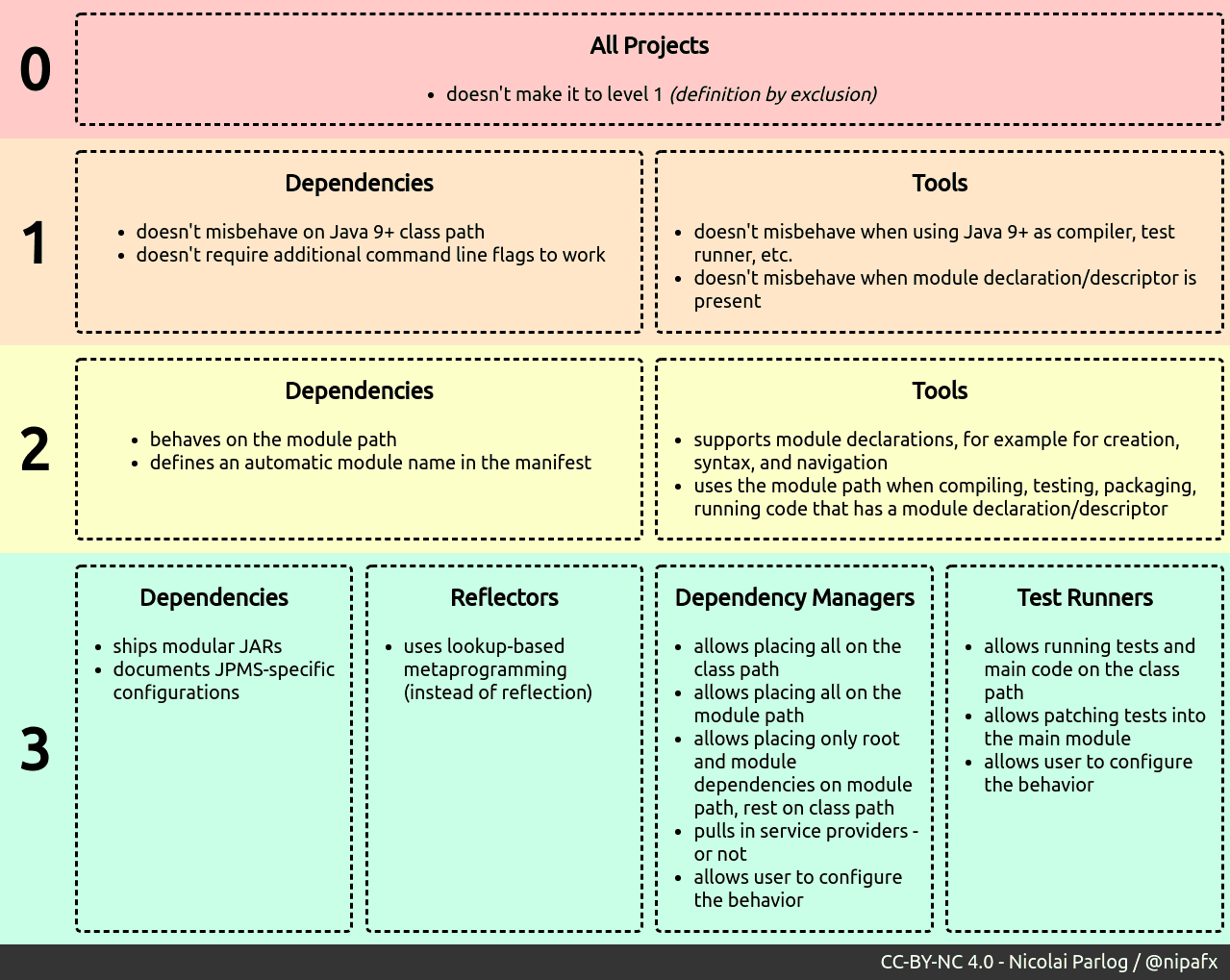

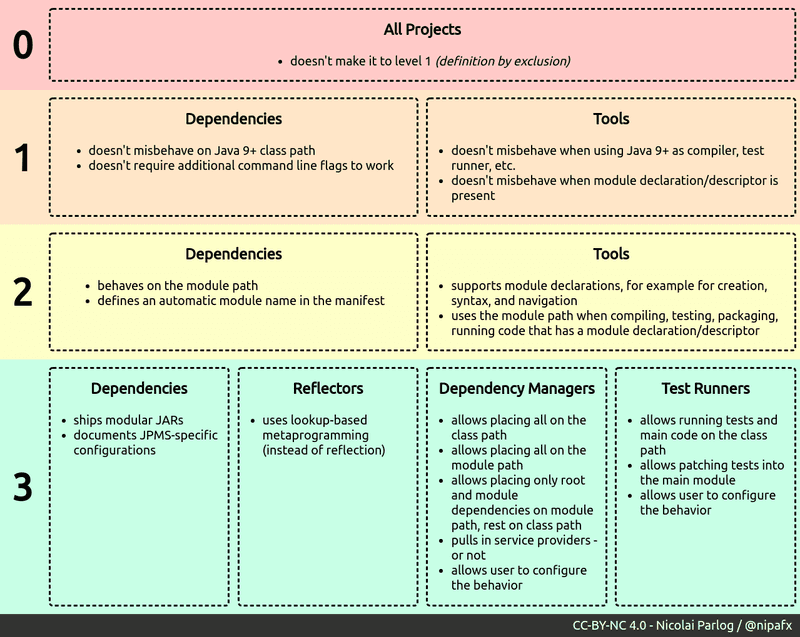

The maturity model defines levels 0 to 3 (higher is more mature) and states requirements for each that a project must fulfill to achieve the respective level. These are cumulative, meaning a project can't be on level 2 if it violates a requirement for level 1. Note that none of them imply that a project requires Java 9 or later - they can all be met by projects that still work fine on older Java versions.

Of course some requirements may not apply to a project's feature set and while most only apply to either tools or dependencies, some projects fall into both categories. Then there are project whose feature sets are irreconcilable with certain requirements - in that case, they may be excused. (But this can't be a cop-out!) That means for a proper assessment, we need to check each level's requirements judiciously against the project at hand.

▚Level 0 (Shock)

Level 0 contains the projects that fail to be fully functional on or with Java 9+. This is mostly a definition by exclusion - everything that doesn't make it to level 1 ends up here.

Examples: Every IDE from 2017 is on this level and Log4J 1.2 (unsupported since 2015, by the way) fails on Java 9+ when parsing the changed version string.

▚Level 1 (Denial): Don't break!

On level 1, projects can deny the module system's existence as long as they don't misbehave because of it. (See this migration guide for how to get there.)

▚Dependencies

Requirements:

- doesn't misbehave on Java 9+ class path

- doesn't require additional command line flags to work

The project must behave on Java 9 and later just as it does on Java 8 and earlier, but only on the class path.

It may access JDK-internal API due to the current default setting for --illegal-access, but must not require additional command line flags.

The project's behavior on the module path is unspecified and may indeed be completely broken.

JARs on this level don't need to define an automatic module name in their manifest.

Example: Most libraries either just work on Java 9 without change or were already updated, but it's tough to find a common one that doesn't also define an automatic module name. Pretty much randomly I ended up with HSQLDB, which as of 2.5.0 has no such manifest entry.

▚Tools

Requirements:

- doesn't misbehave when using Java 9+ as compiler, test runner, etc.

- doesn't misbehave when module declaration/descriptor is present

The tool must be usable with a Java 9 code base that contains modules. That does not necessarily mean that the tool itself must run on Java 9+ (an IDE may run on 8, but allow use of newer versions for the project) and it's even ok to outright ignore the declaration/descriptor and the module path - just don't choke or crash.

Example: IntelliJ 2019.1's test runner is on this level because it runs all tests from the class path, even if the IntelliJ module is a JPMS module. (IDEA-171419 will eventually fix that.)

▚Level 2 (Guilt): Minimal Support

On level 2, projects are aware of the module system and interact with it enough to get their core feature set working with it.

▚Dependencies

Requirements:

- behaves on the module path

- defines an automatic module name in the manifest

On this level, dependencies don't yet need do be modular, but they do have to work on the module path. That also means that they can no longer use JDK-internal APIs as that fails for named modules.

Speaking of module names, JARs need to define theirs with the Automatic-Module-Name manifest entry - see Sander Mak's article for details, but note that compatibility with the module path is not an afterthought, but a prerequisite.

Example: You'll find most of the ecosystem's well-known libraries and frameworks on this level. For example, Log4J 2 ships its non-API artifacts with a defined automatic module name since 2.10.0 (interestingly, the API made it to the next level).

▚Tools

Requirements:

- supports module declarations, for example for creation, syntax, and navigation

- uses the module path when compiling, testing, packaging, running code that has a module declaration/descriptor

There are several ways to distribute dependencies across class and module path. The simplest is to place all on the module path, but that may needlessly put dependencies in a tough spot that are still on level 1. For other approaches, see level 3.

Likewise, there are various ways to run tests of a modular project.

The conceptually simplest is to run the tests as part of the module they're testing by adding the test classes into the main module with --patch-module, adding test dependencies with --add-modules, and making them accessible with --add-reads (I said conceptually simple).

For this level, the exact strategy doesn't matter, though.

Examples: Most of Maven's plugins, particularly Compiler, Surefire, Failsafe, and JAR are on this level. If a module declaration/descriptor is present, they do their usual thing but employ the module system, for example by placing code and dependencies on the module path. Some don't go much beyond minimal support, though. The JAR plugin, for example, supports setting the main class only since 3.1.2, released in May 2019 - until then it simply ignored that capability.

▚Level 3 (Bargaining): Interoperability By Refined And Configurable Support

This is where it's at. Only dependencies on this level fully support the module system and only tools that achieve it can be reliably combined. Otherwise, users end up in situations like the one described in the introduction.

At the same time, this is where things get a little more complex as many requirements only really apply to projects with specific feature sets. That's why this level is split into more detailed categories than just dependencies and tools. This is just for readability, though, a project should still be checked against all requirements.

▚Dependencies

Requirements:

- ships modular JARs

- documents JPMS-specific configurations

On this level, libraries and frameworks ship explicit modules, meaning they come with a module descriptor (possibly in a multi-release JAR). As required by levels 1 and 2, they must still work on the class path and are not allowed to require command line flags to function.

If a project requires their users to modify their module declarations to work with the project, this needs to be well-documented. The most obvious example are tools that use reflection and require their modules to open packages to them (see below for more an that). Ideally, there's a single document that gathers all JPMS-related information in one place.

Examples: Log4J 2 ships its API as a modular JAR since 2.10.0 and all of JUnit 5's JARs are modular since version 5.5.0. They're not the only ones either, check this list of modularized projects.

▚Reflectors

This applies to the many, many, many frameworks using reflection to interact with your code (and every other project that does so):

- uses lookup-based metaprogramming (instead of reflection)

Using the method/variable handle API is in many ways better than reflection: For one, it's more type-safe and performant, but what we care about in this context is its explicitness.

It requires users to provide a Lookup instance, which makes it more robust when used with modules.

(Again, multi-release JARs allow using the Java-9-portion of the API without requiring 9.)

No Example: I know of no project that already uses lookups instead of reflection, but, then again, I didn't go looking either. I'd be glad to be shown projects that adopted this API.

▚Dependency Managers

Tools like IDEs and build tools that deal with dependencies should offer various strategies to distribute them across class and module path:

- allows placing all on the class path (as required by level 1)

- allows placing all on the module path (as described for level 2)

- allows placing only root and module dependencies on module path, rest on class path

- pulls in service providers - or not

- allows user to configure the behavior

The reason for the more complex distribution strategy where only the initial module and all dependencies of a module are placed on the module path is that this results in the minimal set of JARs on the module path.

One less and the module systems errors out.

Any additional JAR on the module path increases the chance that a level-1 JAR ends up there and breaks the project.

This strategy is employed by many Maven plugins, which rely on the Plexus Java project's LocationManager to do that.

For better interoperability, I recommend to other tools to reuse that functionality if at all possible.

Critically, with more than one distribution strategy, the user must be able to easily configure which one to use!

Service providers are often not directly required by any other JAR reachable from the root. Yet, they are usually needed when testing, running, or shipping a project. Tools should allow users to select whether they want to use all services, none of them, or anything in between.

No Example: I know of no tool that offers more than one distribution strategy. If you know one, please enlighten me. 🙂

▚Test Runners

Requirements:

- allows running tests and main code on the class path (as per level 1)

- allows patching tests into the main module (i.e.

main and test code run in the main module; as described for level 2)

- allows user to configure the behavior

These two strategies to run tests are the most established at this point and tools need to offer both because users must be able to test their code on both paths.

As described in Christian Stein's article Testing In The Modular World, there are more ways to run tests:

- a module declaration in the test sources that is merged with the main declaration, which the main code is patched into the test module (i.e.

main and test code run in the test module)

- a module declaration in the test sources that depends on the main module; no patching (i.e.

main and test code in separate modules)

I don't consider them requirements because at the moment they're still experimental. Particularly the last option is really interesting, though, because it allows to test with module boundaries in play, which should be a good fit for integration tests.

Example: Starting with version 3, Surefire has a flag to move test execution to the class path even if a module declaration is present (the only documentation I could find is SUREFIRE-1531).

▚Versions Are Hard

While the model is solid for each individual pair of JDK version and project version, it gets more complicated when you factor in the evolution of Java and its ecosystem. The project version is straightforward to handle: Each release needs to be assessed individually and when talking about a project in general, say Eclipse or Log4J, its assessment is that of the most recent version.

The Java version is more complicated. A project may work fine on Java 11, but fail to do so on Java 12, for example due to removed APIs. Technically, that means it doesn't fulfill level 1's requirements and is back to 0. But that's counter-intuitive because if the problem has nothing to do with the module system, it should not impact the project's maturity rating.

And what about changes that are related to the module system? At the moment, the module system allows code on the class path to access JDK-internal APIs, but that may change in the future. If it does, some projects on level 1 may suddenly require additional command line flags, which kicks them down to 0.

There are three uncomfortable solutions to this:

- Add an asterisk to each (mis)behave-phrase that ignores misbehavior due to changes that are unrelated to the module system. But guess what? Then Log4J 1.2 is on level 1 even though it works on no JVM that contains the module system. That's... odd.

- Add versions to the assessment.

A project may be on level 11-2, but 12-0 because of some change to

Unsafe. But what does that have to do with the module system and hence the project's JPMS maturity? Right, nothing. - Handwave the problem away and hope that developers who employ this model use their common sense to determine how a Java change impacts a project's maturity.

For now, I'm going with 3. Don't make me regret it! 😜