▚Intro

Welcome everyone, to the Inside Java Newscast where we cover recent developments in the OpenJDK community. I'm Nicolai Parlog, Java developer advocate at Oracle and today, I got two topics for you:

- dealing with

null- how to best handle it, what tools can do, and how recent and upcoming language changes impactnull-handling - upgrading past Java 8 on the example of Netflix that recently went from 8 all the way to 16

Ready?

Then... let me tell you why I'm a week late. This episode was supposed to come out a week ago, but the team was busy building the JEP cafe. Every few weeks, my colleague Jose Paumard will open the doors of the JEP cafe to talk about an interesting JDK Enhancement Proposal - the first episode explains where JEPs come from and the next one will be on sealed classes. If you're not yet subscribed to this channel, now's a good time to change that, and if you are, hit the bell icon to get notified as soon as we upload more videos.

Now, let's dive right into null.

▚null in Java

So why talk about null?

What could possibly be new about Ryan Gosling's billion Dollar mistake?

Wait, that doesn't sound right...

Anyway, why null?

One reason is that there has recently been a Reddit thread on the topic that drew almost 300 comments, so... you seem to care about this.

Another reason, I care about this!

I've frequently said that I hate null with a passion, so I jump on every occasion to talk about it.

The most important reason, though, is that Java is changing in that area and that's definitely newsworthy!

▚The Problem with...

On the surface, the problem with null are NullPointerExceptions, right?

Yes, but those are easy to avoid - just add a null-check, maybe return null, and move on!

You just cringed, I saw it.

And for good reason, that's a terrible idea!

Not executing parts of the domain logic probably leads to more bugs, and more subtle ones at that, and returning null just proliferates the problem.

No, the proper solution requires you to first hunt that null reference back to where it came from and decide whether the absence of a value was intentional or a mistake.

And because in Java, null can hide in any reference variable, that backtracking can be a long slog that takes a lot of time.

So that's the trouble with null:

Having to find out whether it encoded intentional absence or a failure state.

Once you've answered that, the fix is usually simple.

▚How to handle...

There are of course a number of ways to handle null.

One of them is not to use it for intended absence:

- for arrays and collections, use empty instances

- for parameters, overload methods and constructors

- for fields, consider inheritance

- for everything else, create domain-specific classes or use

Optional

Another important ailment is to frequently check whether references that aren't supposed to be null actually aren't.

I made a habit of checking all constructor arguments with Objects.requireNonNull - others use the assert keyword for that.

Beyond constructor arguments, consider checking everywhere where you file references away, for example where you add them to a collection.

// NAY

public class Article {

private final String title;

private final LocalDate date;

private final List<Article> recommendations;

public Article(String title, LocalDate date) {

// protracting and proliferating null

this.title = title;

this.date = date;

this.recommendations = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void addRecommendation(Article article) {

recommendations.add(article);

}

}// YAY

public class Article {

private final String title;

private final LocalDate date;

private final List<Article> recommendations;

public Article(String title, LocalDate date) {

// fail fast if null (with static import)

this.title = requireNonNull(title);

this.date = requireNonNull(date);

this.recommendations = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void addRecommendation(Article article) {

recommendations.add(requireNonNull(article));

}

}Then there's documentation.

Whether you document with Javadoc, tests, or intricate coffee stains on design documents, that's a good place to clarify whether an API accepts or returns null.

@Test

void unknownKey_returnsNull() {

var map = createPrefilledMap();

var value = map.get(KEY_WITHOUT_VALUE);

assertThat(value).isNull();

}Finally, there's a ton of tools that want to help you.

Whether it's IDEs, SpotBugs, PMD, NullAway for ErrorProne, the Checker Framework (by the way, links to everything in the description), and probably a few more - they all offer help in this regard.

They might warn you or even fail the build for null-related code smells or they can outright analyze your code to verify that all possibly-null references are checked before accessed.

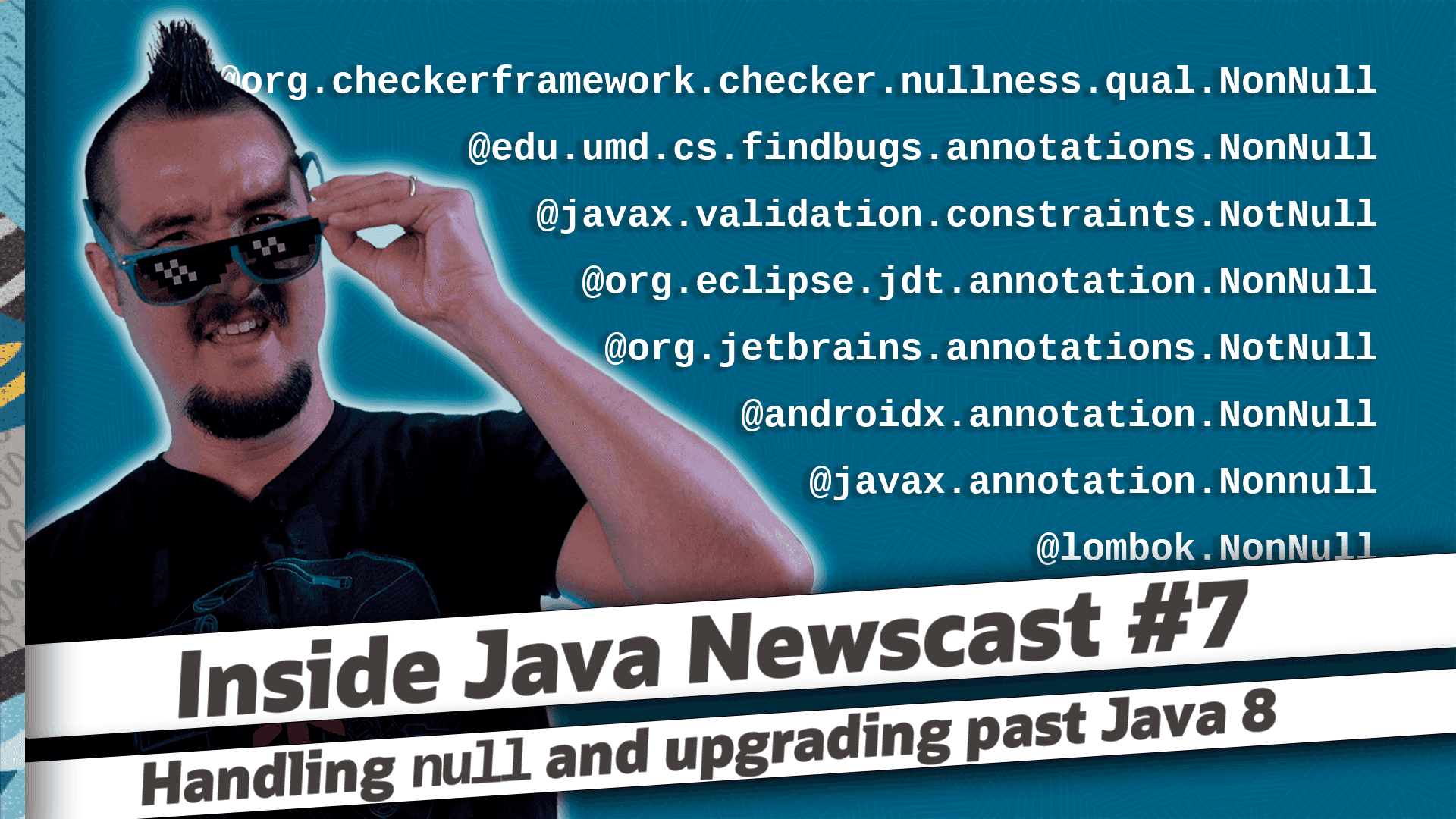

Some interpret the @Nullable annotations provided by JSR 305, some come with their own.

@javax.annotation.Nonnull

@javax.validation.constraints.NotNull

@edu.umd.cs.findbugs.annotations.NonNull

@org.jetbrains.annotations.NotNull

@lombok.NonNull

@androidx.annotation.NonNull

@org.eclipse.jdt.annotation.NonNull

@org.checkerframework.checker.nullness.qual.NonNull

private final String name;So there are already a bunch of tools doing a good job - problem solved, right? Unfortunately not - there's a reason why there's so many of them and why there are many sets of annotations, too. The problem seems simple enough, but when you sit down and work through all the edge cases, you realize that it really isn't. This was the main reason why JSR 305 ran out of steam and was eventually abandoned.

A newer project that tries to tackle this problem is JSpecify, where many of the aforementioned projects work together to create a single set of annotations with fully specified semantics that the tools can all agree upon. It's still in very early stages, so the information on their website and GitHub is a bit sparse. I'll link a slide deck from Google's Kevin Bourrillion, who is working on the project, that's a good walk through the problem space.

▚How changes helps with...

Now let's turn to the Java language itself. It seems an obvious move to just create some annotations and include them in the language, but as I've just explained, it's not that simple. I think at this point, it's fair to say that Java won't move in that direction before one of the aforementioned projects, possibly JSpecify, demonstrates in practice which exact semantics are the best.

But annotations are far from the only way to change how Java treats null.

Current and upcoming language changes have something to say about this as well.

First, there's pattern matching.

In if it uses the instanceof keyword, which historically refused null and so do patterns.

Object obj = null;

// old-style type check

if (obj instanceof String)

// `instanceof` operator

// rejects `null`, so this

// branch isn't executed

Object obj = null;

// modern type pattern

if (obj instanceof String s)

// type patterns

// reject `null`, so this

// branch isn't executedIn switch, if JEP 406 gets released in Java 17 as it is proposed now, the case keyword is used and usually, something like case String s won't match null either (it only will if the variable is declared as String).

More importantly, though, null will be a valid case label and so it will become easier and more natural to handle possibly-null references in switches.

Object obj = null;

// pattern matching in `switch`

switch (obj) {

case String s -> {

// type patterns

// reject `null`, so this

// code isn't executed

}

case null -> {

// easier null handling

// in `switch`

// (unrelated to patterns)

}

case default -> // ...

}Then, Project Valhalla is in this, too.

JEP 401 proposes inline classes, instances of which are either value types or reference types - you can think of them as primitives and their wrappers.

Value types behave a lot like primitives today - for example regarding null because they don't allow it.

primitive class Euro {

private long cents;

// constructor,

// accessor,

// etc...

}

// elsewhere...

// `Euro` refers to the value type

// (~ primitive), so this is a

// compile error:

Euro amount = null;

// `Euro.ref` refers to respective

// reference type (~ "wrapper"),

// so this compiles:

Euro.ref amount = null;So once JEP 401 is merged, we will be able to create classes, whose instances usually aren't nullable - with compiler support and all!

As if Valhalla wasn't splendid enough, fewer problems with null add another reason to yearn for it.

▚Updating past Java 8

If you have followed me for any amount of time - by the way, I'm nipafx on Twitter - you know that I'm convinced that upgrading past Java 8 is possible, necessary, and beneficial. So it's probably no surprise that I was exceedingly happy when I saw Carl Mastrangelo's blog post The Impossible Java 11 make the rounds. In it, he describes how he updated Netflix' Java projects from JDK 8 to 16. Depending on what you heard about moving past 8, you might be expecting long horror stories, technical deep dives, and lots of fiddling. But... nope.

▚It's possible

The post isn't very long and much of it doesn't even describe the update process. Let me read the part that does:

When I joined Netflix, no one told me it was impossible to upgrade from Java 8 to 11. I just started using it. When things didn't work (and they definitely didn't!) on 11, I went and checked if I needed to update the library. I did this as a back-burner project, on my own machine, separate from the main repo. One by one, all the non-working libraries were updated to the working ones. When a library was not Java 11 compatible, I filed a PR on GitHub to fix it. And, plain as it sounds, when there are no more broken things, only working things are left!

And that's it! And it has been my experience as well. Back in summer of 2017, when JDK 9 wasn't even out, I migrated a relatively large and relatively old code base to Java 9 and I did it the same way as Carl: in small steps, always going forward.

▚It's necessary

Earlier, I said that I'm convinced that upgrading past Java 8 is possible, necessary, and beneficial. We covered possible. Now let's talk necessary.

If your project is on Java 8, do you expect it to die within the next 10 to 15 years? Because I don't think you'll find anyone to give you support for that version after that. So unless you are expecting your code base to become irrelevant, you'll have to update eventually - there's just no getting past that.

Like Carl described, updating the Java version is usually preceded by updating your dependencies and tools. And as they release newer versions, that's not gonna get easier if you wait longer. So, generally speaking, the earlier you update, the less work it will be.

▚It's beneficial

But we're already crossing into the beneficial section. Let me cite Carl's post again:

I bring up this story to boost the confidence in others that using the latest and greatest is within grasp. A month ago I updated our code to Java 15, and last week to 16. It gets easier each time. Once you are close to the latest version, it's no challenge to stay there. Since the only breaking changes were hiding JVM internals, and we're no longer using those, it's trivial to update. As a reward, we get all the advanced features (better JIT, GC, language features, etc.) that have been delivered over the past years.

Let's spend a bit of time on that last bit: What do you get for updating? Besides the obvious new language features and improved APIs, an important aspect, particularly if your app is running in the cloud, is better observability, for example thanks to JFR event streaming, and better container support. Also, most projects will see less resource consumption and better performance on newer releases. Finally, a less obvious benefit but one that might come in handy when your organization is struggling to attract Java developers - do you think it makes a difference whether you can offer them to work with JDK 6 or JDK 16?

To close this out, I'll quote Carl one last time:

I encourage you to take a look at updating too, since it is probably easier than you think!

▚Outro

And that's it for today on the Inside Java Newscast. If you have any questions about what I covered in this episode, ask ahead in the comments below and if you enjoy this kind of content, help us spread the word with a like or by sharing this video with your friends and colleagues. Now, it's time to check out th JEP cafe - it's right there. I'll see you again in two weeks. So long...