It's Christmas time, at least where I'm living, but Santa came early and already delivered us a big bag of brand new and improved Java features for JDK 22:

statements before this and super, multi-source-file programs, G1 region pinning, FFM API, stream gatherers, and a bunch more.

So let's unpack, shall we?

▚Intro

Welcome everyone to the Inside Java Newscast, where we cover recent developments in the OpenJDK community. I'm Nicolai Parlog, Java Developer Advocate at Oracle, and today we're gonna talk about all the features of the upcoming Java release. JDK 22 comes out in March 2024 and is forked today, so the feature list is final.

Says the script I wrote a few days ago, but things may have changed since then. You may remember that I had to do a whole second episode on JDK 21 half a year ago to cover last-minute additions and removals. So please check the pinned comments after watching this video - it will let you know whether anything changed. Down there in the description box, you'll also find links to the many videos and articles I'll mention later. And why not leave a like while you're at it? It really helps getting this video to more Java developers.

Ok, enough preamble, we'll start with the features that are set in stone and that you can use to your heart's content to improve your projects. Let's dive right in!

▚Final Features

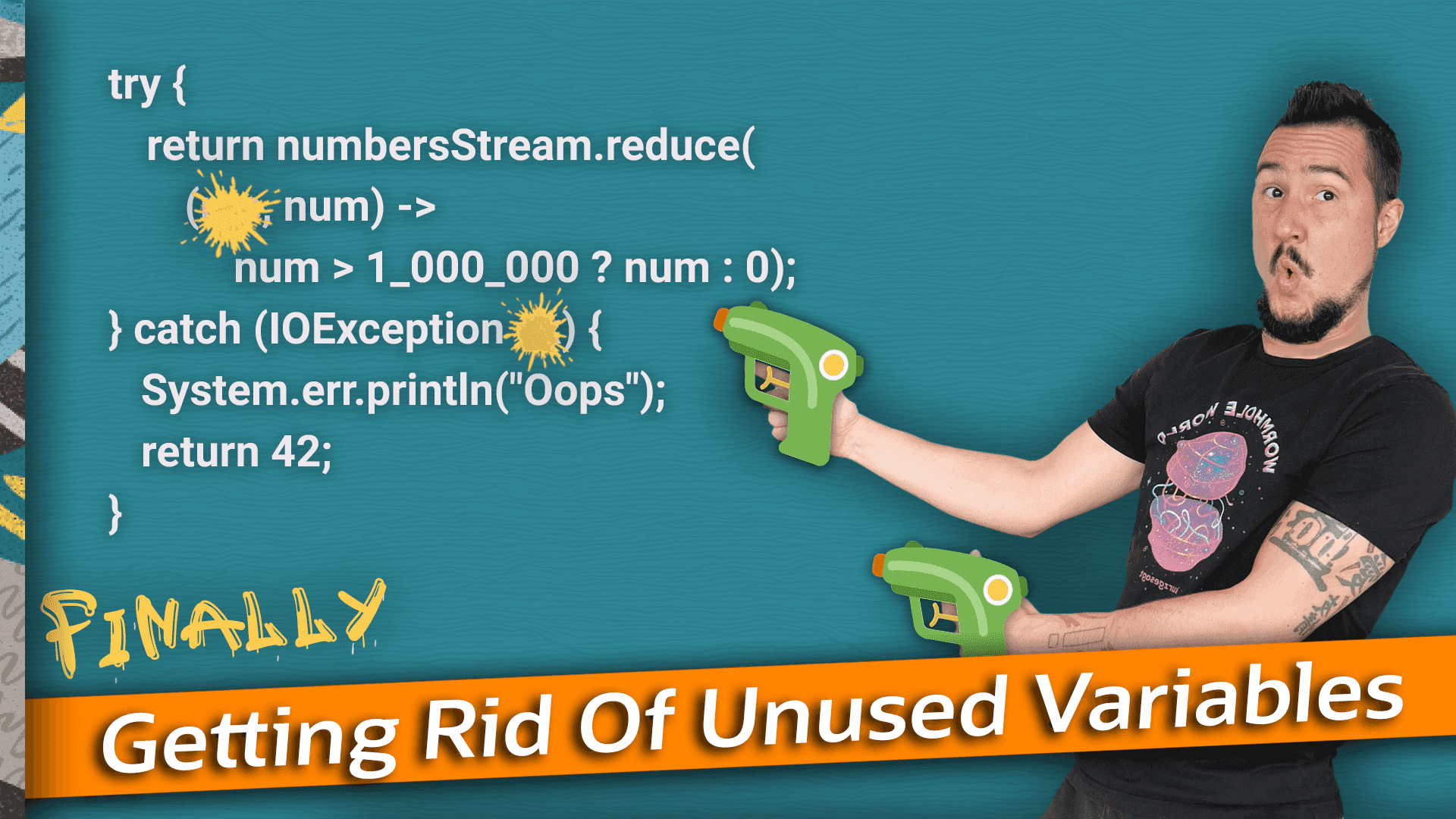

▚Unnamed Patterns And Variables

We've looked into unnamed patterns and variables in detail in Inside Java Newscast #46. The TL;DR is that you can use the single underscore to mark variables that you do not intend to use. With local variables...

int _ = sumGearRatios(input);pattern variables...

if (obj instanceof

Circle(Point _, int radius)) {

// ...

}resources in try-with-resources blocks...

try (var _ = ScopedContext.acquire()) {

// ...

}for loops...

for (int _ = 0; ; ) {

// ...

}caught exceptions...

try {

// ...

} catch (IOException _) {

// ...

}and lambda parameters you can replace the variable name with the underscore.

int someLargeNumber = numbers

.reduce((_, num)

-> num > MAX_VALUE/2 ? num : 0);In patterns, you can go one step further and elide the type of an unnamed variable as well.

So, to create a Function<Integer, String>, for example, that ignores the input, you can write a lambda Integer _ -> "foo", var _ -> "foo", or just _ -> "foo".

Whichever variant you choose, you can never reference such variables, so there can't be any collisions and so you can have as many underscores in the same scope as you want.

Unnamed variables are particularly important when switching over a sealed type.

Such a switch needs to be exhaustive, meaning it must cover all possible types, but it should avoid a default branch or permitting new subtypes doesn't lead to the desired compile error.

Without a default branch, expressing the same "defaulty" behavior for a few different types is cumbersome, though, because branches like case Circle c and case Rectangle r cannot be combined - if they could, neither c nor r could be used because you'd never know whether the shape is a circle or a rectangle.

switch (shape) {

case Triangle t -> highlight(t);

case Circle c -> { /* ... */ }

case Rectangle r -> { /* ... */ }

}

switch (shape) {

case Triangle t -> highlight(t);

// compile error

case Circle c, Rectangle r -> { /* ... */ }

}With unnamed variables, the situation is different:

You cannot reference them anyway, so it doesn't matter which type the variable actually has and so case Circle _, Rectangle _ works and you can thus express defaulty behavior with a default branch, sorry, without a default branch - that's the important part.

This is the way to go and that's why unnamed variables are more than a nice-to-have feature.

switch (shape) {

case Triangle t -> highlight(t);

// compiles! 🥳

case Circle _, Rectangle _ -> { /* ... */ }

}Unnamed patterns and variables have previewed in JDK 21 and JDK 22 finalizes them without changes.

▚G1 Region Pinning

The G1 garbage collector divides the heap into regions and treats every region separately during collections. Depending on the kind of collection and the state of the region, different things can happen, but generally speaking, objects in a region may be moved elsewhere. For objects that only the JVM uses, that's fine - it will find them in their new locations. But that's not the case for native code like C or C++ that gets called from Java. If the data it references gets moved around, terrible things will happen.

To prevent that, Java code can mark objects that it passes to native code as critical and then it's up to the garbage collector to leave them in place. A simple way to make sure they're not moved is to just not collect any garbage while any critical object is held and that's what G1 has been doing until JDK 21. To quote JEP 423:

This has a significant impact on latency: [...] In the worst cases users report critical sections [that are sections of code that hold critical objects] blocking their entire application for minutes, unnecessary out-of-memory conditions due to thread starvation, and even premature VM shutdowns .

Thanks to that JEP, the impact on latency is much lower on JDK 22. G1 will now collect garbage even while critical objects are held, but avoid the regions tht contain them.

It's good that G1 will perform better when Java passes on-heap objects to native code, but of course there's another option: Move such data off-heap, which brings us to the foreign function and memory API.

▚Foreign Function & Memory API

At this point, so much has been said about the foreign function and memory API, or FFM for short, that I will spare you anything but the briefest of summaries, which is:

FFM allows you to interact with native code and to manage off-heap memory and it does both of that much better than the Java Native Interface and ByteBuffer, respectively.

For more details, check out these links:

You'll find them all in the description.

FFM is Project Panama's crowning jewel and has been in the works for years now with the first bits and pieces showing up in incubation in JDK 14 and its first complete preview in JDK 19. JEP 454 finally finalizes it in JDK 22 with only minor changes over JDK 21.

▚Multi-Source-File Programs

Since Java 11 you can take a .java file and instead of compiling it and then running the resulting class file, throw it directly at the Java launcher:

java Prog.java will compile it in memory and then run Prog's main method.

So far this feature has been limited to single-source-file programs, meaning that if Prog.java references another source file, say Helper.java, the class wouldn't compile and hence no code would be executed.

// in Prog.java

public class Prog {

public static void main(String[] args) {

var greeting = Helper.parse(args);

System.out.println("Hello, " + greeting);

}

}

// in Helper.java

public class Helper {

public static String parse(String[] args) {

return args.length == 0

? "World"

: args[0];

}

}# on command line

$ java Prog.java

> Prog.java:4: error: cannot find symbol

> var greeting = Helper.parse(args);

> ^That changes in JDK 22 with JEP 458.

The launch command will stay the same, but now the launcher will look up files that are referenced in the initial source file, for example Helper.java if Prog.java references it.

That means when a new developer who's still learning the ropes or a more experienced developer who's experimenting or really anybody who just just throws together some code wants to go from a single source file to splitting up their code into several files, there's no hold-up.

They, or we, can keep coding in this simple environment that requires no series of terminal commands, no build tool, no IDE.

# on command line with JDK 22

$ java Prog.java

> Hello, World

$ java Prog.java Java_22

> Hello, Java_22I'm super thrilled about this and there are quite a few details to explore. We'll do that in an upcoming Inside Java Newscast - take a second to subscribe if you don't want to miss it. And this isn't even the only on-ramp feature in JDK 22! Let's take a look at the other one, but for that we have to go into preview features.

▚Previews And Incubations

Next up are previews and the seemingly never-ending incubation of the vector API. You need a few command-line flags to experiment with these features - I put a link in the description that explains which ones.

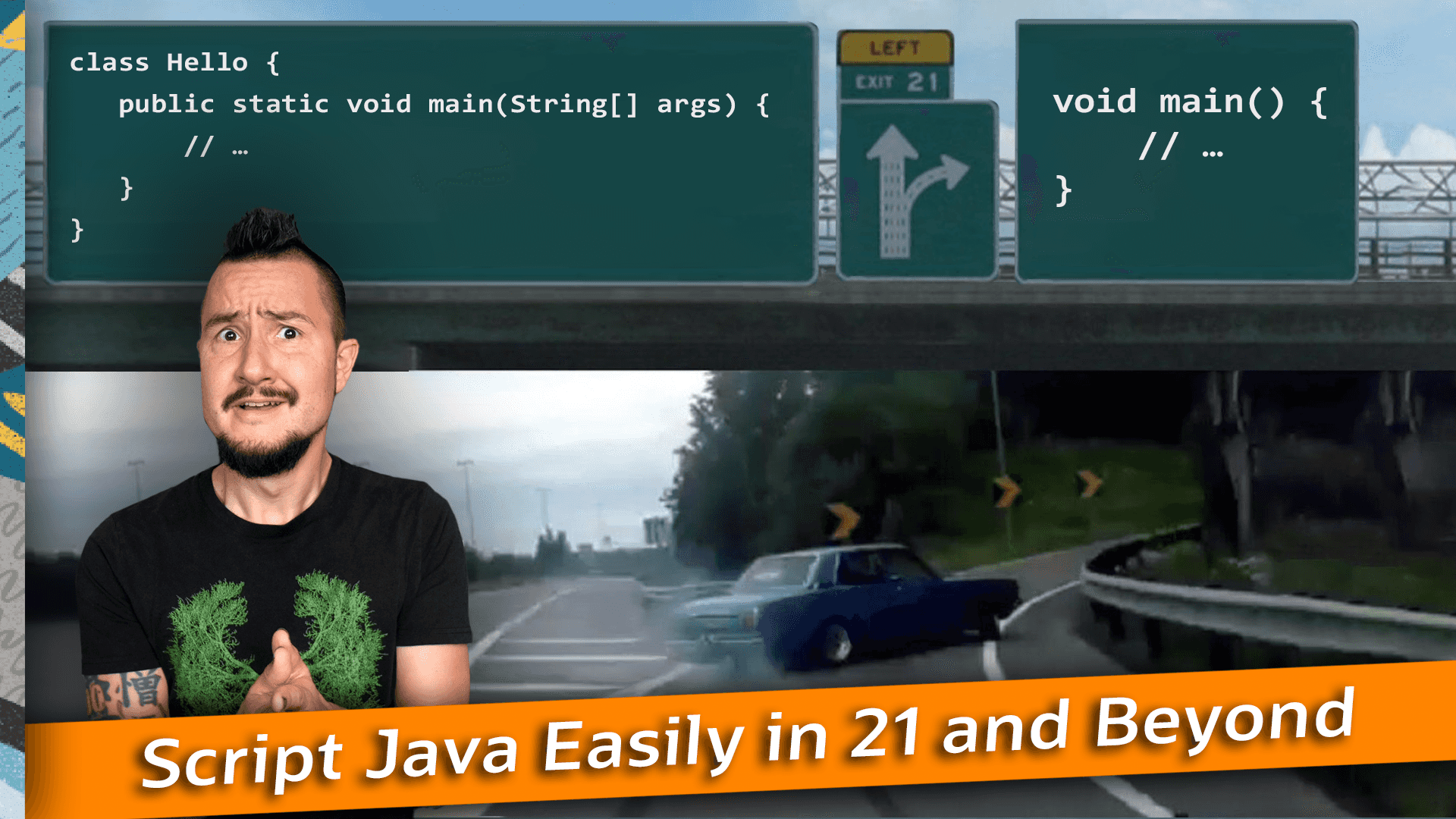

▚Simpler Main

A simpler main method that doesn't need to be static nor have a String[] args parameter, nor even be in a class - yes, a top-level method in a Java source file - first previewed in JDK 21 and we've examined it closely in Inside Java Newscast #49.

// this is the complete source

// file, i.e. there's no class

String audience = "World";

void main() {

System.out.println(

createGreeting());

}

String createGreeting() {

return "Hello, Simple Main!";

}Based on feedback, JEP 463 evolved how this feature is embedded in the specification and in the JDK implementation and the name evolved from Unnamed Classes and Instance Main Methods to Implicitly Declared Classes and Instance Main Methods. These changes under the hood require a second preview in JDK 22 but all practical aspects remain unchanged. This together with single and now multi-source-file programs. chef's kiss

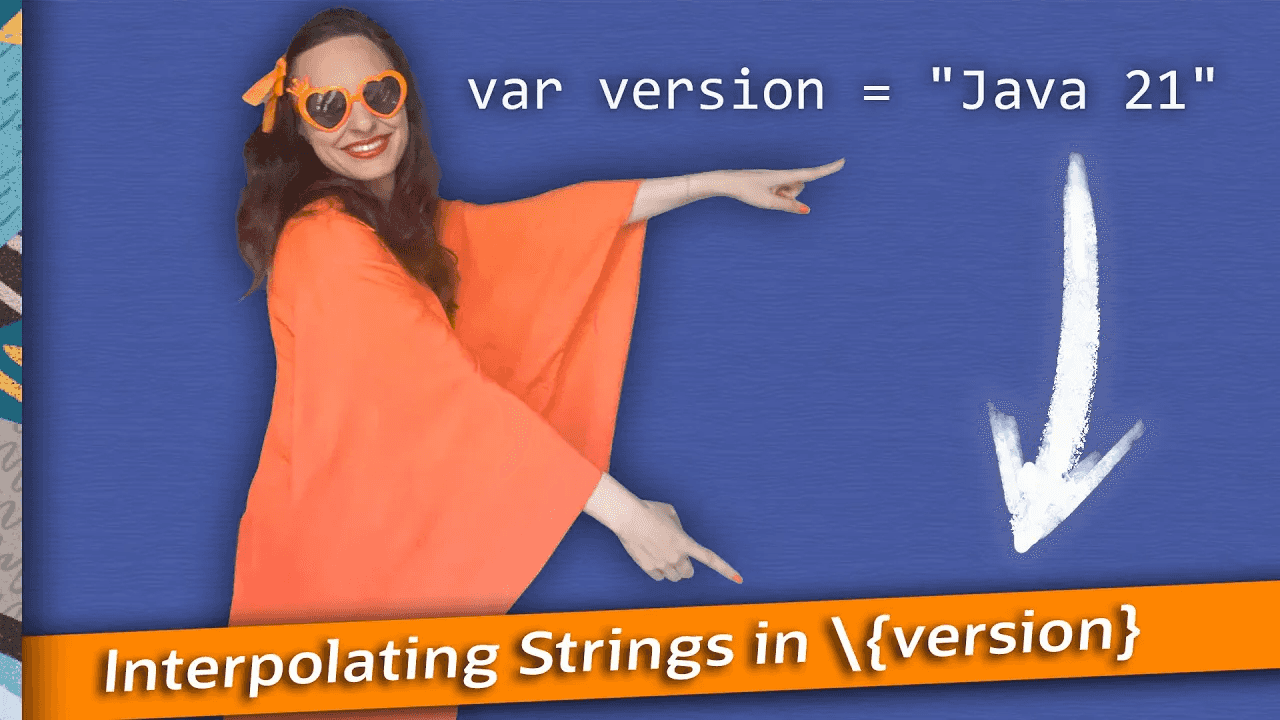

▚String Templates

String templates see their second preview in JDK 22. They are practically unchanged since their first preview in 21 and so Ana's in-depth presentation in Inside Java Newscast #47 is still the best way to learn about them.

Here, I'll leave you with this beauty, which lets you print to System.out with just PRINT."$string":

public static final StringTemplate.Processor<Void, RuntimeException> PRINT = template -> {

System.out.println(STR.process(template));

return null;

};One character less than even Python, which I hear is a very important metric for some folks. Oh wait, I forgot the static import. Nevermind, then, but still cool.

▚Vector API

The vector API is still waiting for value types to roll around.

Until then, it will keep incubating with the occasional improvement:

In JDK 22, its seventh incubation, btw, it can now access heap MemorySegments that are backed by an array of any primitive type, not just of byte.

▚Statements Before this(...) And super(...)

You know how in a constructor that must call a superclass constructor with super(...) or wants to delegate to a constructor in the same class with this(...), the explicit constructor invocation, meaning the super(...) or this(...) call, must be the first statement?

That limitation is gone!

Previewing for the first time in JDK 22, JEP 447 introduces the so-called prologue: statements before the explicit constructor invocation.

The statements in the prologue run in a new pre-construction context, which is strictly weaker than a static context. That just means that you can do everything in a prologue that you could do in, for example, a static method and even a bit more.

So if you want to validate arguments before delegating to another constructor or process them to create new arguments that you then pass on, you can now do that! Neat!

I'll go into more detail on this in an upcoming Inside Java Newscast, probably next year - you know what to do.

▚Class-File API

JEP 457 introduces Java's own bytecode parsing, generating, and manipulating API. It has a data-oriented design that pivots on an immutable representation of a class' bytecode with sealed interfaces and records and an API that allows tree traversal and streaming to read and generate bytecode.

The class-file API is intended to replace ASM as the de-facto standard to manipulate bytecode, so that ASM is removed as an upgrade blocker and updates, for example from Java 25 to 29, become easier. If that chain of statements escalated too quickly and you want to better understand how this API will lead us into a brighter future, check out Inside Java Newscast #56, and if you want to learn how it works, remind Jose the next time you see him that he should make a JEP Cafe about it.

▚Structured Concurrency and Scoped Values

The structured concurrency and scoped value APIs are seeing their second preview in JDK 22 and are both unchanged compared to JDK 21. If you have a code base that already uses virtual threads, I highly recommend you check them out. Take a look at JEP Cafes 13 and 16 to learn how to use structured concurrency and scoped values, respectively, and give it a go. And if you want to contribute back to OpenJDK, a great way to do that is to report your experience, positive or negative, to the Loom mailing list - link in the description.

▚Stream Gatherers

I love using the stream API. In fact, I'm doing Advent of Code this year, and so far each of my solutions has a stream pipeline as an integral part. But when using the API a lot, you start missing operations - I'm sure this has happened to you. JEP 461 mostly fixes this by introducing the gatherer API, which previews in JDK 22.

Gatherers are to intermediate operations what collectors are to terminal operations: a general construct that allows you to implement your logic within the stream pipeline.

And, like collectors, you will usually call a static method to get an implementation of the new interface Gatherer and pass that to the new gather method on Stream.

A gatherer consists of four operations:

- the

Initializer, which creates an initial state, should you need that - the

Integrator, which consumes stream elements and emits them to the next stage and optionally updates the state - the

Finisher, which gets called when there are no more stream elements to consume and can operate on the final state to emit a few more elements - and the

Combiner, which is needed in parallel streams to combine two states into one

With that you can implement operations like runningAverage, fixedGroups, slidingWindow increasingSequences, and more.

Check out episode #57 for the theory and this video for practice.

▚Outro

And that's it for JDK 22. Do you have a favorite feature? I do but it was really hard to pick. I'll explain why in the pinned comment. Don't forget to check that out and to like and subscribe and I'll see you again in two weeks - so long...