Can you believe that this Inside Java Newscast has an episode number 1 with six zeroes? One, zero zero zero, zero zero zero - that is so cool! So, for this jubilee episode, should we have some fun? Experiment a bit, explore the boundaries of modern Java, and maybe come up with a dirty trick or two? I say, we should!

▚Intro

Welcome everyone, to the Inside Java Newscast, where we cover recent developments in the OpenJDK community. I'm Nicolai Parlog, Java Developer Advocate at Oracle, and today we're gonna use, misuse, and abuse a few of Java's latest features. This requires that you already know and understand them, so I'll sometimes post a link to another video, so you can study up if you need to.

Also, some of what we'll end up doing is a bit dirty, so please don't take this as advice to use such code at work. We're here to have fun and to experiment, not to write code for customers. If you don't appreciate the joy of exploration for its own sake, that's fine, but then this episode is not for you, so please no "Why would you do that?" comments. And that includes Reddit - I see you!

Got it? Then let's have some fun!

▚Expandable Sealed Types

Sealed types let us ensure that we know all implementations of an interface.

Say we're modeling HTML and want to have a type for divs, another for paragraphs, another for spans, and so forth, then it makes sense to create an interface HtmlElement that they all implement and that is sealed and permits exactly them as subtypes.

sealed interface HtmlElement permits Div, Paragraph, Span { }

record Div(/*...*/) implements HtmlElement { }

record Paragraph(/*...*/) implements HtmlElement { }

record Span(/*...*/) implements HtmlElement { }

String tag(HtmlElement element) {

return switch (element) {

case Div _ -> "<div>";

case Paragraph _ -> "<p>";

case Span _ -> "<span>";

};

}But what if we want to allow users of our project to expand this type hierarchy?

To do that, keep in mind that a type that extends a sealed type must itself be sealed, final, or explicitly non-sealed.

And the latter allows arbitrary implementations, so it can act as an extension point in our hierarchy.

So for custom HTML elements, we could permit a non-sealed interface CustomElement extends HtmlElement and then users extend from there.

sealed interface HtmlElement permits CustomElement, /*...*/ { }

non-sealed interface CustomElement extends HtmlElement { }

String tag(HtmlElement element) {

return switch (element) {

case Div _ -> "<div>";

case Paragraph _ -> "<p>";

case Span _ -> "<span>";

case CustomElement _ -> "<🤷🏾♂️>";

};

}This creates an issue, though. If we build a fully-sealed hierarchy, we're free to implement all operations on it externally, meaning as methods on some other classes that take types from our hierarchy as input, switch over them, and treat each according to the operation's needs. Compared to adding operations as methods on these types directly, this has the major advantage that we can easily add new operations without changing the types.

But what about those custom types? How do we treat them in our operations?

No really, I'm asking.

I don't know any approach that always work elegantly.

I can tell you that in the CustomElement extends HtmlElement-example, I ended up adding a method to CustomElement that resolves it to an HtmlElement.

So in that case, I expect every custom element to be able to express itself in HTML and then all my other logic can build on that.

I'm quite happy with that solution for that specific case but it's obviously not generally applicable.

non-sealed interface CustomElement extends HtmlElement {

HtmlElement resolve();

}

String tag(HtmlElement element) {

return switch (element) {

case Div _ -> "<div>";

case Paragraph _ -> "<p>";

case Span _ -> "<span>";

// let's hope there's no

// infinitive recursion 🤞🏾

case CustomElement c ->

tag(c.resolve());

};

}▚Nesting Switches

The HTML example I just gave? It's actually a bit more complicated: I ended up having to distinguish between three different elements types:

- the aforementioned HTML elements

- the custom elements users could provide

- a limited number of internal elements like pure text

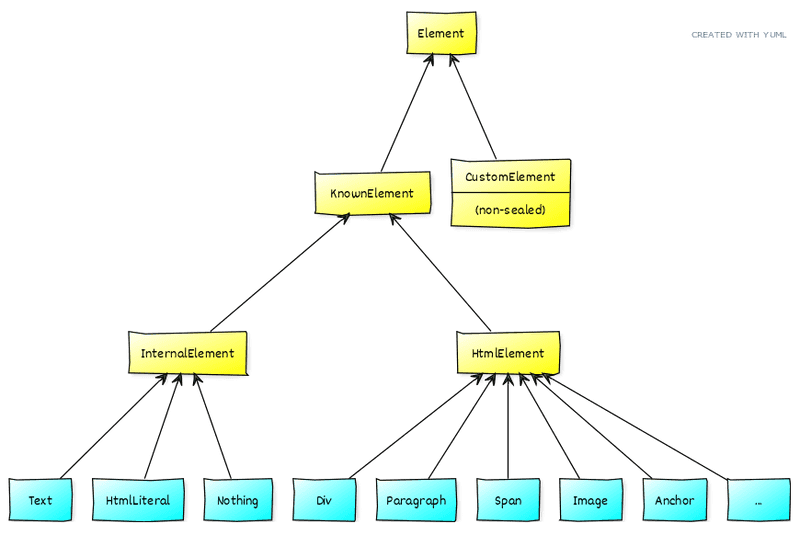

The hierarchy I chose was a top-level interface Element which permits KnownElement and CustomElement.

We already discussed CustomElement before, which is the only non-sealed interface in this hierarchy.

KnownElement is further split into HtmlElement and InternalElement, both of which permit a dedicated set of records that implement them.

Now, an operation that accepts an Element needs to switch over that.

It can say case KnownElement -> ... and case CustomElement -> ... and that covers all cases but is borderline pointless - I want to operate on those records after all.

So instead I wrote a case for each record implementing HtmlElement, then a case for each implementing InternalElement, and a final one for CustomElement.

Element element = // ...

switch (element) {

// HTML elements

case Div div -> ...

case Paragraph p -> ...

case Span span -> ...

case Image img -> ...

case Anchor a -> ...

case ...

case Text text -> ...

case HtmlLiteral html -> ...

case Nothing nothing -> ...

case CustomElement custom -> ...

}That covers all possible implementations and the compiler is happy.

But here's the thing:

That's a pretty long switch and in an effort to make it easier to understand, I added a comment // HTML elements above those cases, a comment // internal elements above those, and an empty line above case CustomElement because I couldn't bring myself to adorn it with the comment // custom element.

Element element = // ...

switch (element) {

// HTML elements

case Div div -> ...

case Paragraph p -> ...

case Span span -> ...

case Image img -> ...

case Anchor a -> ...

case ...

// internal elements

case Text text -> ...

case HtmlLiteral html -> ...

case Nothing nothing -> ...

case CustomElement custom -> ...

}And then something freaky happened. The unmoored essence of Uncle Bob appeared and screeched "all comments are failures" with a voice like fingernails on a chalk board until I removed them. Because I can express this in code, right?

The switch over the element can consist of three cases for three interfaces HtmlElement, InternalElement, and CustomElement and then the first two cases can point to a nested switch that covers that respective element.

The cool part is that, unlike with comments, I can't accidentally put a new record branch into the wrong block.

This really is self-documenting code.

Element element = // ...

switch (element) {

case HtmlElement html -> switch (html) {

case Div div -> ...

case Paragraph p -> ...

case Span span -> ...

case Image img -> ...

case Anchor a -> ...

case ...

}

case InternalElement in -> switch (in) {

case Text text -> ...

case HtmlLiteral html -> ...

case Nothing nothing -> ...

}

case CustomElement custom -> ...

}But... it's also very silly to add these functionally pointless intermediate switches, right? That's not bothering just me, right? Right?!

▚Reverse Instanceof

You already know that instanceof now allows us to declare a variable of the checked type.

So element instanceof Div div means we get to use the variable div.

But where do we get to use it, where is it "in scope" as the language nerds would put it?

The answer is: everywhere the condition is true.

Classically, that's in the if branch ...

HtmlElement element = //...

if (element instanceof Div div) {

// `div` is in scope

}... but what happens when we invert the condition?

So if (!(element instanceof Div div)).

Then in the if branch, element is of the wrong type and div is not in scope but in the else branch it is.

HtmlElement element = //...

if (!(element instanceof Div div)) {

// `div` is NOT in scope

} else {

// `div` is in scope

}Or, maybe we throw an exception from the if branch, don't have an else branch, and then div is in scope everyhwere after the if.

😮

HtmlElement element = //...

if (!(element instanceof Div div))

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

// `div` is in scopeSo if you're one of those people who (like me) like to put their validation checks at the beginning of a method and a type check is one of them, you can negate the type check, throw an exception if the negation is true, and then happily use a variable in the rest of the method that is not declared as a parameter, is not on the left-hand side of a statement but somewhere on the right in the midst of an if.

Use, misuse, abuse?

You tell me!

▚Stream Filter By Type

With all that more direct handling of types, I noticed that my need to filter streams by type has increased.

So given a stream of HtmlElements, I may want to retain only the Div instances.

The filter-then-map combo was always too cumbersome for me, though, so here's what I ended up with:

Stream<HtmlElement> elements = // ...

Stream<Div> divs = elements

.filter(Div.class::isInstance)

.map(Div.class::cast);A StreamUtils class for this and other kinds of handcrafted operations with a static method keepOnly that takes a Class<T> instance as input and returns a Function<E, Stream<T>> in the form of a lambda that takes an element of type E and uses the class instance to check whether the element is actually of type T, in which case it returns a stream of just that element cast to T, otherwise the empty stream.

On the use site we statically import the method and just write flatMap(keepOnly(Div.class)).

public static <E, T> Function<E, Stream<T>> keepOnly(Class<T> type) {

return e -> type.isInstance(e)

? Stream.of(type.cast(e))

: Stream.empty();

}

Stream<HtmlElement> elements = // ...

Stream<Div> divs = elements

.flatMap(keepOnly(Div.class));Since JDK 16, I could use mapMulti instead of flatMap to avoid the Stream instance with just one element and gatherers offer another alternative, but I never bothered to update the code to that.

▚Ad Break!

Short ad break! On March 19th, JDK 22 will be released and we'll celebrate that on this channel with a five-hour live stream starting at 1700 UTC. We'll go over JDK 22's final features, the on-ramp efforts, preview features, and we get an update on Graal as well as on projects Babylon, Loom, and Leyden. And we'll even do a bit more. Brian Goetz will give a short keynote, Mark Reinhold will be there, Alan Bateman and Ron Pressler, and lots of other interesting folks. Keep an eye on this channel in the days before to spot the live stream once it's announced and I'll see you there.

▚Switching Over Optional

Sealed classes and pattern matching are great to model and process alternatives and there's one fundamental alternative at the core of programming that other languages often model this way: something or nothing.

A decade ago, in the absence of these language features, Java went a different way, though: a final class with methods like map and orElse that abstract over the alternatives of presence and absence - Optional.

What would that look like with pattern matching, though?

Let's imagine a sealed interface Option<T> that permits the two implementing records:

Nonewithout any componentsSome<T>with a componentT value

sealed interface Option<T> permits None, Some { }

record None<T>() implements Option<T> { }

record Some<T>(T value) implements Option<T> { }Then, when we have an Option instance in hand, we switch over it and write a case None _ for the absent case and a case Some(var value) for the present case, which then processes the unpacked value:

Option<String> opt = // ...

var text = switch (opt) {

case None _ -> "Empty";

case Some(var value) -> "Contains: " + value;

};Look, ma, no map or orElse but the compiler still makes sure I handle both cases and unlike with lambdas passed to ifPresentOrElse, the branches can even throw exceptions!

Too bad we can't use that today.

Or can we?

Just add a static factory method over to Option that takes an Optional<T> and returns an Option<T>.

Then we can write switch(over(optional)) and do our cases.

sealed interface Option<T> permits None, Some{

static <T> Option<T> over(Optional<T> opt) {

return opt

.<Option<T>> map(Some::new)

.orElse(new None<>());

}

}

Optional<String> opt = // ...

var text = switch (over(opt)) {

case None _ -> "Empty";

case Some(var value) -> "Contains: " + value;

};Or, better yet, we wait for Java to allow static patterns and then we don't even need Option anymore and can match Optional directly.

Now, you might be comparing that approach to using map, flatMap, etc. or simply ifPresent with get and are probably wondering in which situations you'd prefer pattern matching over the functional or over the imperative approaches that Optional already allows.

Good.

Optional<String> opt = // ...

var text = switch (opt) {

// speculative syntax (there's not even a JEP for this)

case Optional.empty() -> "Empty";

case Optional.of(var value) -> "Contains: " + value;

};▚Text Block Line Endings

This is a counterintuitive one. What are text blocks for? To write strings that span multiple lines, right? Yes, or to write really long single line strings. Hear me out.

If we end a text block line with a lone backslash, there won't be a line break there and one way to use this is to turn a regular string literal that gets too long for a single line into a text block but prevent the unwanted line breaks with trailing backslashes.

var block = """

this \

is \

one \

line\

""";

var literal = "this is one line";

block.equals(literal); // trueAnother way to use this is to play with indentation management. If we place a text block's closing delimiter (the three quotation marks) on its own line, we can use their position relative to the rest of the text block to mark which part of the indentation is code formatting and which part should be present in the resulting string. But having the closing delimiter on its own line also adds a newline character to the end of the string and sometimes you just don't want that.

var text1 = """

string contains

no indentation

""";

text1.endsWith("\n"); // true

var text2 = """

both lines start

with a tab

""";

text2.endsWith("\n"); // trueI think the intended way to handle this is to put the delimiter on the last line and then add the indentation we need by calling String::indent on it.

But that method uses spaces for indentation and we all know only sociopaths do that, so we need another solution, which is... yeah, you got it, to add a lone trailing backslash to the text block's last line.

var text = """

both lines start

with a tab\

""";

text.endsWith("\n"); // falseIs this still use or already misuse? I'll come back to that in a minute. But since we're already talking about text block line endings, let me address the Windows users among you.

Hey, are you ok?

Recent years were tough, I know.

Java no longer auto-detects latin1 as default encoding, the centered layout in Windows 11, learning that Linux runs games faster, having to build your project in WSL2 because even a virtualized ext4 is faster than Windows' native file system, and now it's 2024 - the year of Linux on the desktop.

I bet... I bet dealing with all that isn't easy.

But don't give up, all is not lost.

The \r\n line endings will always be there for you.

And, if you need to get those in a text block, remember: you can just end each line in \r and Java will do the rest for you.

var text = """

windows \r

line \r

endings \r

""";▚Good Or Dirty?

So which of these tricks are good and which are dirty? And for the dirty ones, which of them could be used anyway if push comes to shove and which are just so bad that they should be killed by fire? I have some thoughts on that but I'm also of the opinion that it's often contextual and that more relevant than somebody telling you their opinion on this is you thinking through the implications yourself. So instead of priming you by sharing my thoughts here, I'll put them in a comment down there and I won't pin it, so it sits between everybody else's opinions on this, which I'm really curious about, so please comment away.

Also, I wanna try something. I recently noticed that YouTube adds a glow to the like and subscribe buttons when people in the video say certain phrases. I wanna give that a try. So, could you please exit your fullscreen and scroll those buttons into view?

Ok, now, please subscribe and smash that like button. And if you have some self respect to spare, please send it my way, I clearly lack any. So long ...