▚Intro

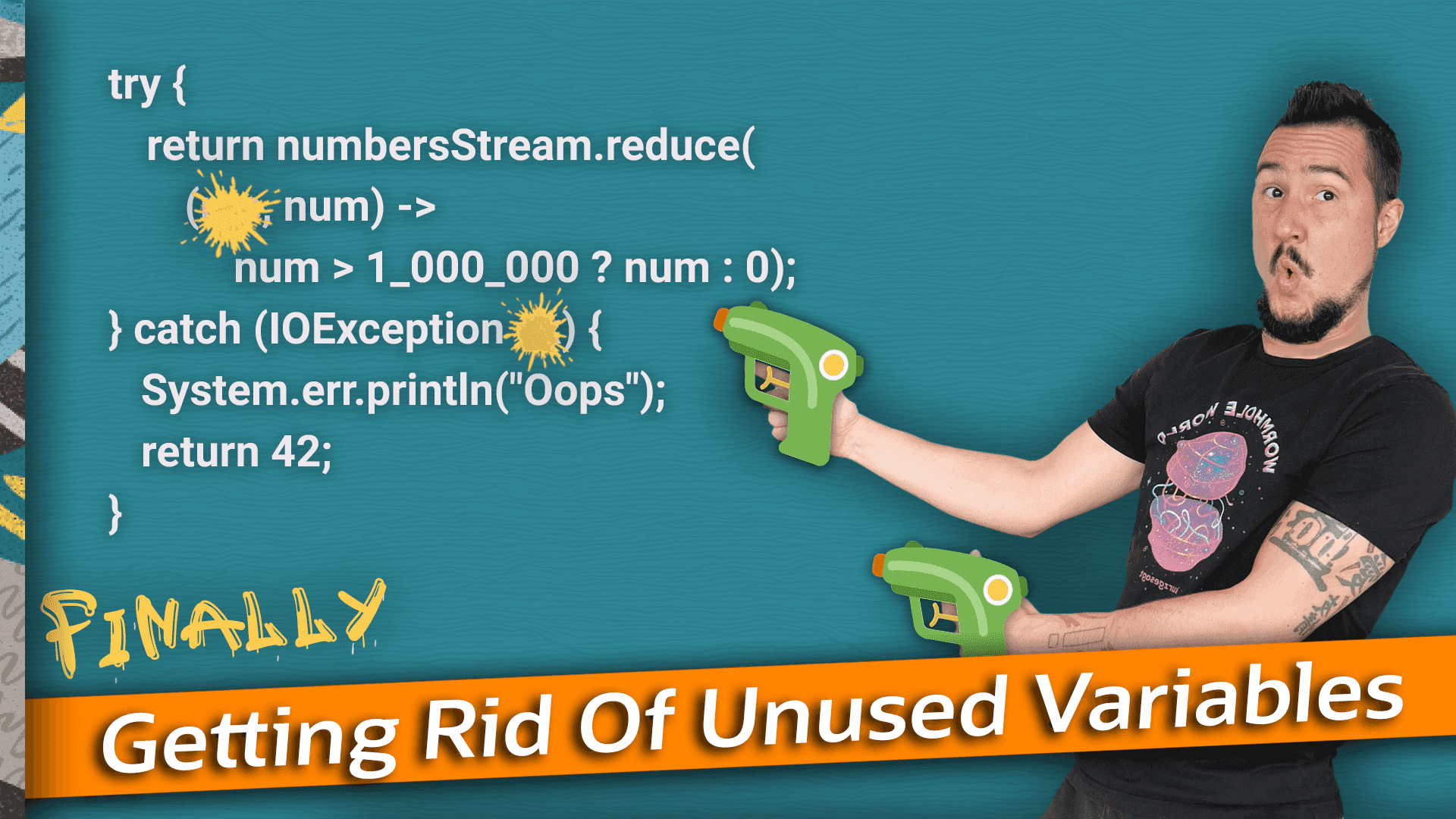

Welcome everyone, to the Inside Java Newscast where we cover recent developments in the OpenJDK community. I'm Nicolai Parlog, Java developer advocate at Oracle, and today we're gonna get rid of all those variables you had to declare even though you didn't want to use them. No need for this first parameter of that lambda? Now it's gone! Don't care about the exception? Gone! No use for all those destructured record components? Guess what? Gone!

IntStream numbers = // ...

int someLargeNumber = numbers

.reduce((💥, num) -> num > MAX_VALUE / 2 ? num : 0);

try {

// ...

} catch (IOException 💥) {

System.err.println("That didn't work. 🤷");

}

if (shape instanceof Triangle(var a, 💥, 💥))

System.out.println("Triangle point A: " + a);Because today we're gonna talk about JEP 443: unnamed patterns and variables. They're mainly about convenience and clarity, and we'll go over that first, but you'll also see why they will play a critical role in writing maintainable pattern matches.

Ready? Then let's dive right in!

▚Unused

▚The Situation

Unused variables are pretty annoying: IDEs turn them grey or give you squiggly lines, code linters give you stink eye, and your colleagues are tattling about yours behind your back. And they all have good reason! Until they don't. Because sometimes it just can't be helped.

Maybe you're implementing a BinaryOperator but only need the second argument.

Maybe your error handling doesn't depend on the specific exception you're catching.

Maybe the resource in your try-with-resources block only needs to be opened and closed but you don't want to interact with it.

Then there's the rare for-each loop where you don't actually need the loop variable.

And in even rarer cases you may want to capture a method's return value even though you don't want to use it.

These situations are pretty uncommon (although the unused lambda parameter pops up a bit more often in my code) but if you've already experimented with record patterns, you know that not needing all the destructured components is actually pretty common. And deconstruction itself will become more common. At the moment, it only works with records in pattern matching but both of those limitations may be relaxed in the future: Classes in general may get explicit deconstructors and deconstruction on assignment and in for each loops is also on the horizon.

// made up syntax! ↓↓↓↓↓ unused

Triangle(var a, var b, var c) = fetchTriangle();

System.out.println("A & B: " + a + " & " + b);

Collection<Triangle> triangles = // ...

// more made up syntax! ↓↓↓↓↓ unused

for (Triangle(var a, var b, var c) : triangles)

System.out.println("A & B: " + a + " & " + b);So the future brings more deconstruction, which will bring more unused variables.

▚The Workarounds

But what can you do if you want or - more likely - need to declare a variable that you're not going to use?

Some devs give the variable a regular name and simply ignore it.

Others punish it by cutting its name short to a single letter - no self-documenting name for you!

You could name it unused.

But none of these are ideal.

(result, number) -> number > 1_000 ? number : 0

( r, number) -> number > 1_000 ? number : 0

(unused, number) -> number > 1_000 ? number : 0Here's what I do: Java 8 deprecated the use of the single underscore for variable names and Java 9 forbade it - it's been a compile error ever since.

// legal in Java 7-

// warning in Java 8

// error in Java 9+

int _ = 0;So I use the double underscore for such variables.

(__, number) -> number > 1_000 ? number : 0Until I need two of them in the same scope - then I have to up it to three. But that doesn't keep the IDEs and linters from complaining either.

So, all in all, not a great situation. It hasn't been a big problem in the past but with deconstruction patterns becoming more common, it will become very annoying very quickly. So somebody needs to do something about it!

▚Unnamed

▚The Solution

Thankfully the good people working on Project Amber are on it! I just said that Java 8 deprecated and Java 9 forbade the use of the single underscore, right? That happened for exactly this scenario! (Which is where I got the idea to use two underscores from. Yeah, I'm not very creative.)

So Project Amber brought forth JDK Enhancement Proposal 443: unnamed patterns and variables.

In a nutshell, you can use the single underscore in place of a variable name or a pattern but you can never refer to it - you can't "declare" String _ and then call _.length().

And because _ does not actually refer to a variable, you can use it several times in the same scope.

If you don't need that lambda parameter nor that exception nor those two record components, you can use _ for all of them!

try {

// something

} catch (IOException _ ) {

Stream<Shape> shapes = // ...

return shapes.reduce(( _ , shape) -> {

if (shape instanceof Triangle(var a, _ , _ ))

return a;

else

return shape.center();

});

}Marking unused variables this way has a number of benefits: The most obvious one is that we no longer have to come up with names for them. (I can already feel the stress falling away.) Then it removes visual clutter and clearly communicates to your colleagues that the variable is unused. The same is true for compiler and linters, so we can expect fewer warnings from them. And then there's the pattern matching bonus that I mentioned in the intro but before we get to that I want to go over a few details of the proposal.

▚The Details

Technically, the proposal consists of three parts:

- unnamed variables

- unnamed variables in patterns

- unnamed patterns

Let's take it one by one. Unnamed variables replace the variable name in

- a local variable declaration

- a resource specification of a try-with-resources statement

- the header of a basic or enhanced for loop

- an exception parameter of a catch block

- a formal parameter of a lambda expression

If you want, you can use unnamed variables with var and just like there, there must always be an initializer, for example an expression on the right-hand side of a local variable declaration.

Declaring an unnamed variable does not place a name in scope, which are fancy words for it can't be written or read after it has been initialized.

And since nothing is placed in scope, there's no shadowing and you can declare multiple such variables.

Unnamed pattern variables replace the variable name in, wait for it, patterns. Namely, in type and record patterns, because that's all we have at the moment. They do require explicit types, though.

If you want to get rid of the type information, too, basically writing var _, you have an unnamed pattern and don't the need the var after all - just replace the full type-and-variable-name with _.

Unnamed patterns bind nothing but match everything, which is why they don't make sense at the top level and so are forbidden there:

They can only be used in nested positions in place of a type or record pattern.

▚Patterns

I mentioned that this will play a critical role in writing maintainable pattern matches. In particular, I was referring to unnamed patterns in switches because they make it more convenient to avoid default branches.

Now, why would you want to do that? In order to implement behavior that differs by type, you want to switch over a sealed supertype and then exhaustively and explicitly list all possible subtypes.

sealed interface Shape

permits Triangle, Rectangle, Circle { }

var shape = // ...

switch (shape) {

case Circle c -> highlight(c);

case Triangle t -> { }

case Rectangle r -> { }

}That way, when a new subtype gets added, you can follow the compile errors to all the switches that need to be updated.

sealed interface Shape

permits Triangle, Rectangle, Circle, Line { }

var shape = // ...

switch (shape) {

case Circle c -> highlight(c);

case Triangle t -> { }

case Rectangle r -> { }

// no `Line` branch ⇝ compile error

}Now, if you'd have used a default branch, the switch would still be exhaustive and you wouldn't get a compile error - the code would silently run into that branch whether that's correct or not.

sealed interface Shape

permits Triangle, Rectangle, Circle, Line { }

var shape = // ...

switch (shape) {

case Circle c -> highlight(c);

default -> { }

// default for `Line` ⇝ no error

// but is it the correct behavior? 🤷

}Ok, so we need to avoid default branches by explicitly listing all possible subtypes.

But sometimes you just have "defaulty" behavior for a few of those branches and so you want to combine them.

But while multiple case labels are legal since Java 14, multiple named patterns are not.

Because case Triangle t, Rectangle r doesn't make any sense - you could use neither t nor r because the compiler doesn't know which one matched.

sealed interface Shape

permits Triangle, Rectangle, Circle { }

var shape = // ...

switch (shape) {

case Circle c -> highlight(c);

// compile error

case Triangle t, Rectangle r -> { }

}And this is where unnamed patterns come in!

With them, you can use multiple unnamed patterns in a single case label: case Triangle _, Rectangle _.

You still don't know which pattern matched, but since you can't refer to any variable anyway, that doesn't matter.

sealed interface Shape

permits Triangle, Rectangle, Circle { }

var shape = // ...

switch (shape) {

case Circle c -> highlight(c);

// simple default behavior 🥳 plus

// compile error when adding `Line`

case Triangle _, Rectangle _ -> { }

}So here's my recommendation for switches over a sealed supertype:

- handle all subtypes explicitly

- do not use a

defaultbranch - if you have default behavior, use multiple unnamed patterns in a single case to match the relevant subtypes

This way, you have just a bit more code than with a default branch but in return the compiler will point you to this switch if you add a new subtype.

To me, beyond the convenience and clarity JEP 443 will doubtlessly bring to our code, this is the biggest benefit because it really helps write more maintainable code.

When we'll start doing that is not settled, though - the JEP is not yet targeted to a release.

(By the way, have you noticed that we've moved past the must-have list of pattern matching features and got to the nice-to-haves? Yeah, Java has pattern matching now. Incredible.)

▚Outro

And that's it for today on the Inside Java Newscast. If you like these videos, do me a favor and let YouTube know. In two weeks, Ana will tell you all about the biggest improvement Java's strings have ever seen - yes, bigger even than text blocks. Subscribe and ring the bell, so you won't miss it. I'll see you again in four weeks. So long...